Tag technology raises fundamental issues. Nada and Andrew Kakabadse outline some of the key questions.

New technologies can creep up on us. They attract attention at the time they’re announced and then go to ground. Those we find no use for are discarded. Others mutate, evolve, find new applications or combine with other technologies. Potential uses proliferate as the technology gradually colonises its opportunity space, in a process of dissemination, development, and adoption that unfolds below the threshold of public awareness.

Two decades ago Mark Weiser wrote in Scientific American that ‘The most profound technologies are those that disappear.’ He referred to technologies that ‘weave themselves into the fabric of everyday life until they are indistinguishable from it.’ They can disappear not only because, like the mobile phone, they become familiar, but also because they are so small or unobtrusive they are practically invisible.

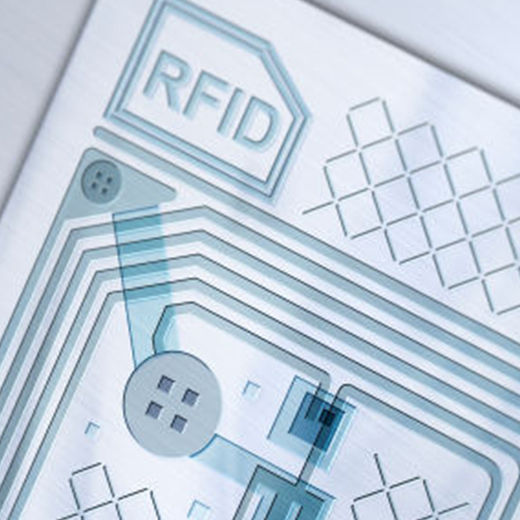

Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) tag technology is an example of the latter.

Radio frequency codings were used for ‘identification of friend or foe’ in World War II. The first RFID tags emerged in the 1950s, in the nuclear industry, to identify and track radioactive material.

Miniaturisation opened up more applications. In the 1990s RFID tags were attached to materials and products, to improve stock control and supply chain management, used by libraries for tracking and sorting books, implanted in pets and other livestock and, after a pioneering deployment in Oklahoma in 1991, they became commonplace in toll road payment systems throughout the US.

In 1998, Kevin Warwick, professor of cybernetics at the University of Reading, implanted himself with an RFID tag, for an experiment. This was an important milestone. Tags attached to, or embedded in inanimate objects used, or carried by humans, such as products and credit cards, raised no ethical or philosophical issues not raised by other technologies, such as closed circuit television. But when technology pierces the skin and invades the sovereign state of the human body it enters a domain awash with ethical, moral, political and philosophical controversy. Highly charged terms such as ‘human branding’ enter the discourse; Orwellian visions of mind and body control are evoked; cries of outrage are heard about invasions of privacy; aggressive covert surveillance and infringements of civil liberties.

In 2004 the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved an RFID implant, VeriChip, about the size of a grain of rice, for medical purposes. Nightclubs in Rotterdam in the Netherlands and Barcelona in Spain already offer implants to customers for entry and payment purposes. Some claim the Obamacare health act makes subdermal RFID implants mandatory for all US citizens.

RFID technologies promise enormous benefits, in areas ranging from security and health monitoring, to business efficiency. But there is a dark side to the technology; a potential for abuse. To those with no love of individual freedom and self-determination it opens up seductive new vistas for control, manipulation and oppression.

To get an idea of how people feel about subdermal tags and provide a starting point for a much-needed debate about their use we spoke to people representing four groups; those who have implants; those contemplating implants for their children for safety or security reasons; policy advisors who have considered recommending implants to clients; and opinion leaders.

The first two groups (implanted or contemplating implants) had not considered ethical issues. Some regretted this. They felt they had made errors of judgement they could have avoided if the issues had been explained. All participants felt insufficient information on health and ethical issues was provided to those contemplating RFID implants. Some participants strongly advocated more pilot testing before further adoption. Others were worried about what they felt was the poorly-controlled, opaque nature of the manufacture of tag implants.

All participants felt that the widespread use of RFID implants was inevitable, but there was a general unease about what they saw as the covert, subtly coercive manner in which implant technology was being introduced by governments and big business.

The study suggests that a number of specific questions need to be answered in each case:

The wider use of RFID implants in humans may be inevitable, but it should not go unchallenged. A full debate is needed about ethical and health issues, to ensure deployment of implants complies with Article 3 of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which asserts the right to ‘life, liberty, and security of person.’

Andrew Kakabadse was included in the 2011 Thinkers50. Nada Kakabadseis Professor in Management and Business Research at the University of Northampton’s Business School. For more information visit www.kakabadse.com

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| LANG | 9 hours | Linkedin set this cookie to set user's preferred language. |

| nsid | session | This cookie is set by the provider PayPal to enable the PayPal payment service in the website. |

| sp_landing | 1 day | The sp_landing is set by Spotify to implement audio content from Spotify on the website and also registers information on user interaction related to the audio content. |

| sp_t | 1 year | The sp_t cookie is set by Spotify to implement audio content from Spotify on the website and also registers information on user interaction related to the audio content. |

| tsrce | 3 days | PayPal sets this cookie to enable the PayPal payment service in the website. |

| x-pp-s | session | PayPal sets this cookie to process payments on the site. |

| __cf_bm | 30 minutes | This cookie, set by Cloudflare, is used to support Cloudflare Bot Management. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| l7_az | 30 minutes | This cookie is necessary for the PayPal login-function on the website. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| CONSENT | 2 years | YouTube sets this cookie via embedded youtube-videos and registers anonymous statistical data. |

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_10408481_1 | 1 minute | Set by Google to distinguish users. |

| _ga_ZP8HQ8RZXS | 2 years | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| NID | 6 months | NID cookie, set by Google, is used for advertising purposes; to limit the number of times the user sees an ad, to mute unwanted ads, and to measure the effectiveness of ads. |

| test_cookie | 15 minutes | The test_cookie is set by doubleclick.net and is used to determine if the user's browser supports cookies. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |

| yt-remote-connected-devices | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt-remote-device-id | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt.innertube::nextId | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| yt.innertube::requests | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| DEVICE_INFO | 5 months 27 days | No description |

| loglevel | never | No description available. |

| m | 2 years | No description available. |

Thinkers50 Limited has updated its Privacy Policy on 28 March 2024 with several amendments and additions to the previous version, to fully incorporate to the text information required by current applicable date protection regulation. Processing of the personal data of Thinkers50’s customers, potential customers and other stakeholders has not been changed essentially, but the texts have been clarified and amended to give more detailed information of the processing activities.