In a world where inclusion fatigue and leadership burnout frequently collide, a simple question continues to resonate across boardrooms and strategy retreats: why, after decades of effort, does the ‘leaky pipeline’ continue to see women and minorities exit or be overlooked for key opportunities, resulting in their underrepresentation at the highest echelons of decision-making?

In 2024-2025, we set out to better understand what helps – and what hinders – the progression of diverse talent into leadership roles. Through in-depth conversations with 64 senior leaders from UK-based multinational companies, the Hult International Business School/Moving Ahead study explored the organisational factors that either support or block career advancement. We referred to these as tailwinds (the forces that propel diverse talent forward) and headwinds (the barriers that slow progress and contribute to the leaky pipeline).

Our goal was to identify ways organisations can develop leadership and talent pipelines that offer a diverse range of capabilities, perspectives, and life experiences, ultimately strengthening leadership benches and future-proofing strengths through diversity in our inter-connected world.

The turning point in our work arrived unexpectedly. During a focus group, a senior leader in a worldwide financial firm leaned forward and said something that changed the entire conversation.

“For years we have invested so much time, resources and effort at D&I, and yet, when we look at the outcomes, we don’t have leadership benches that provide diversity of talent, thought and experience, so we have to ask the question – why is it so hard to turn the dial on this? Why is it so difficult to do?”

That question lit a fire and became the catalyst for deep exploration into how traditional inclusion strategies can be reimagined. We were so intrigued by the strength of debate that we embedded this very question into our interviews with the study participants.

Our findings revealed a general consensus: leaders are of the view that currently, EDI is often (a) poorly understood (b) perceived as top-down and imposed (c) seen as a ‘sticking-plaster’ (d) ineffective at promoting systemic change and (e) does not enjoy the support or buy-in of all stakeholders. We find leaders are searching for ways to regenerate, revitalise, and reform their approaches – in ways that build stronger leadership benches and promote strength and unity through diverse talent. The impetus is coming from within.

What could help us shift the dial? We suggest one way forward lies in taking a systemic regenerative approach.

This means changing the direction of the lens. We need to look at ourselves, our organisation, our systems, and the culture that defines us, and having seen our reflections we need to be committed to build anew from the inside-out.

Culture was in fact a constant theme to emerge from our work. As one leader in a City of London finance multinational put it:

“The high ideals written into traditional EDI strategies often flounce and fail when they meet the hard realities of “on the ground cultures” – it all comes back to our culture.”

Talking about culture presents an immediate problem, because ‘culture’ is in itself a highly contested term, considered by many practitioners to be a ‘flaky’ concept which is difficult to grasp.

Our view is that culture is nebulous but can be ‘made real’. Looking at it through the lens of McKinsey’s famous 7S model – Structure, Systems, Strategy, Style, Staff, Skills, Shared Values – is a good place to start.

These seven elements form the backbone of organisational culture. When misaligned, they often work against the building of strong, robust, and diverse leadership benches.

For example, let’s take S for systems, and consider the systems we have in place for decisions on promotion and reward. One senior leader in a UK investment bank cites an example where a poor promotion decision was made on the basis of perception:

“The perception was that the two women shortlisted would not be able to travel internationally due to childcare. They were the best talent, but the decision was not to promote. Ultimately I think we have lost out and this is bad for business.”

Strategy can be another key area of sub-optimal effectiveness. For decades the traditional paradigm in the UK has been the familiar EDI strategy. Our hundreds of hours of conversations with leaders suggest that, however well intentioned, such strategies are often perceived by stakeholders as imposed, as bolt-on’s, and often not horizontally or vertically aligned with other strategies.

Very few organisations want to be seen as unfair, or as sites of disadvantage and favouritism. Stakeholders don’t set out to sabotage their organisations and the quest for diverse capability-led leadership talent. However, our research does show that when we look at organisations through the lens of the 7S’s, they frequently contain multiple sites of disadvantage, favouritism, and decisions that are ultimately bad for business. As one female leader in the engineering sector says: “We’re often talking about the right thing. We’re not always doing the right thing”.

So, how can we go about systemic regenerative work on this issue?

A systems approach offers an alternative: a root-and-branch, holistic method consistent with the principles of regeneration. Systems thinking means looking at how everything connects – from policies and practices to mindsets and values – and identifying where change needs to happen.

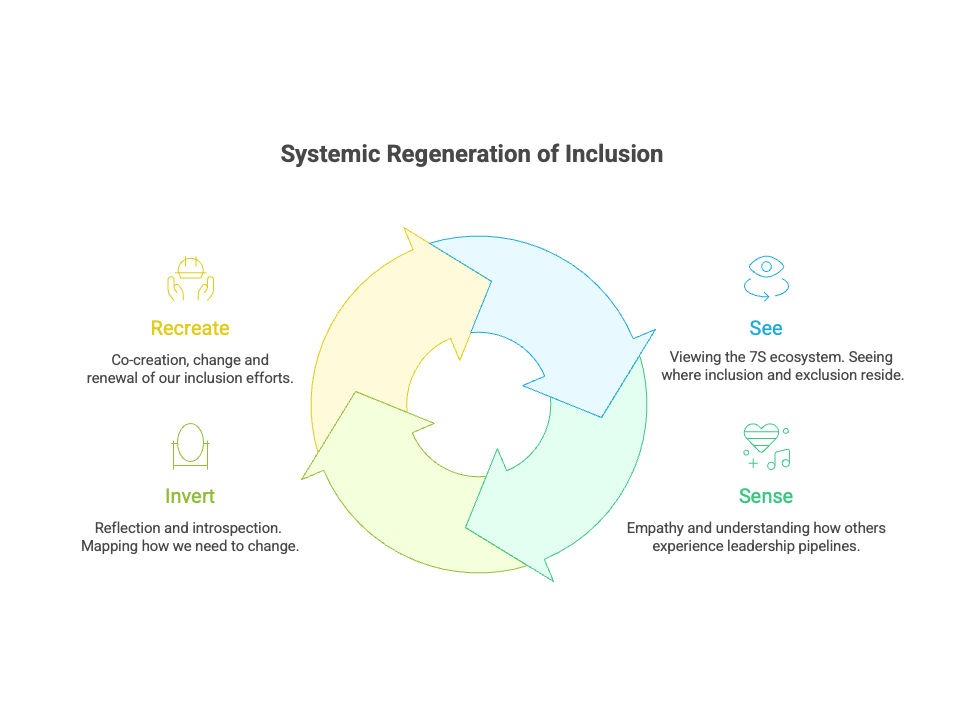

Rather than tinkering with processes or tweaking structures, systems thinking, as advocated by Otto Scharmer for example, asks organisations to shift, where necessary, the mindsets and consciousness that shapes decisions. Put simply, to see where change is needed in the way we think about, talk about and ‘do’ inclusion. The key stages of a systems approach to inclusion are visualised here:

To understand the nature of the headwinds we need to ‘see the system’ and view the web of behaviours, logics, patterns, and practices that hold talent back from progressing. Where are the barriers, how do they manifest, and how do they connect throughout our 7Ss in ways that sustain leaky pipelines?

Our research shows headwinds reside within the 7Ss. For example:

Style: Leadership norms often favour traditionally masculine traits. Many women (and some men) feel pressured to lead in ways that don’t feel authentic, which can lead to frustration and disengagement.

Systems: Promotion criteria may reward constant availability, unintentionally excluding those with different working patterns or responsibilities.

Shared values: Inclusion is sometimes seen as HR’s responsibility alone. But real change happens when senior leaders actively champion it, and when everyone understands how they can contribute to these values in their roles.

Systems thinking encourages us to explore these areas honestly and thoroughly. Tools like systems mapping can help leaders visualise how these elements connect – and where the gaps are. That’s where meaningful change begins.

Having seen, the next step involves ‘sensing’ what these pockets of resistance feel like for those affected. This provides the impetus for closing the knowing-doing gap; moving from cognitive knowing that systemic blockages are real and present to empathy that provides the impetus for action. Leaders must feel the system from perspectives other than their own.

In practice, this means:

Many organisational headwinds endure because leaders attempt change from the same mindset that created the problem. Inverting the system means developing reflective practices that challenge how leaders pay attention, listen, and assign value.

Transformational change emerges when leaders acknowledge the picture that is emerging, and rather than run away from the (uncomfortable) revelations, they step forward and embrace the challenge to regenerate. Pivotal to this regeneration is a commitment to recreate by co-creating the future that wants to emerge, not the past they are trying to fix. This is a crucial step that needs to be genuinely inclusive; because currently our research shows a perception among some stakeholders that traditional EDI paradigms have excluded them.

Organisations can establish inclusion labs where stakeholders help to broaden out the scope of inclusion, and prototype ways to unlock the leadership talent of all people. These labs dissect current policies, practices, behaviours (everything visible above the waterline) and reform and regenerate these in ways that are informed by the new knowledge and lessons learnt from the listening steps. In other words, they reveal the unseen stories below the waterline.

We saw examples where one organisation created knowledge banks of ‘story dashboards’ which acted as a repository of lived experiences in their firm. These were an amazing resource for sharing and informing, and acted as a way-in to change. It’s difficult not to buy-in to the stories of colleagues! These prototypes can generate regenerative tailwinds – practices that renew and transform the way we do inclusion strategy, through new insights and new logics.

When we apply systems thinking to our headwinds-and-tailwinds framework, a clear message emerges:

Regenerative organisations learn to see and sense themselves and furthermore sense a new future – one that creates a turbo-charged organisation where capability and talent thrives. We cannot change the headwinds until we transform the consciousness that helps reinforce them. Regeneration begins when leaders learn to see, sense, and steward a new system, a new way of ‘doing’ inclusion that is based on an authentic understanding of the living system that is your organisation, and that is genuinely inclusive in co-creating solutions.

Dr. Aidan McKearney is an associate professor in human resource management and a faculty member at Hult International Business School. His research and publications include topics on D&I (diversity & inclusion), in particular areas around sexuality and gender and how organisations can adopt more strategic approaches to build and develop inclusive cultures for all.

Dr. Neha Pathak is a senior academic leader, educator, and researcher with over 15 years of experience across international business schools. Currently serving as senior associate dean at Hult International Business School, she specialises in curriculum innovation, experiential learning, and faculty development, and is an advocate for regenerative leadership and systemic change in higher education.

References

Hult International Business School and Moving Ahead: 2025. ‘Headwinds and Tailwinds: Exploring the experiences of women in the ExCo Pipeline.’

Scharmer, O. (2016). Theory U: Leading from the Future as It Emerges. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| LANG | 9 hours | Linkedin set this cookie to set user's preferred language. |

| nsid | session | This cookie is set by the provider PayPal to enable the PayPal payment service in the website. |

| sp_landing | 1 day | The sp_landing is set by Spotify to implement audio content from Spotify on the website and also registers information on user interaction related to the audio content. |

| sp_t | 1 year | The sp_t cookie is set by Spotify to implement audio content from Spotify on the website and also registers information on user interaction related to the audio content. |

| tsrce | 3 days | PayPal sets this cookie to enable the PayPal payment service in the website. |

| x-pp-s | session | PayPal sets this cookie to process payments on the site. |

| __cf_bm | 30 minutes | This cookie, set by Cloudflare, is used to support Cloudflare Bot Management. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| l7_az | 30 minutes | This cookie is necessary for the PayPal login-function on the website. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| CONSENT | 2 years | YouTube sets this cookie via embedded youtube-videos and registers anonymous statistical data. |

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_10408481_1 | 1 minute | Set by Google to distinguish users. |

| _ga_ZP8HQ8RZXS | 2 years | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| NID | 6 months | NID cookie, set by Google, is used for advertising purposes; to limit the number of times the user sees an ad, to mute unwanted ads, and to measure the effectiveness of ads. |

| test_cookie | 15 minutes | The test_cookie is set by doubleclick.net and is used to determine if the user's browser supports cookies. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |

| yt-remote-connected-devices | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt-remote-device-id | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt.innertube::nextId | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| yt.innertube::requests | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| DEVICE_INFO | 5 months 27 days | No description |

| loglevel | never | No description available. |

| m | 2 years | No description available. |

Thinkers50 Limited has updated its Privacy Policy on 28 March 2024 with several amendments and additions to the previous version, to fully incorporate to the text information required by current applicable date protection regulation. Processing of the personal data of Thinkers50’s customers, potential customers and other stakeholders has not been changed essentially, but the texts have been clarified and amended to give more detailed information of the processing activities.