By Stuart Crainer and Des Dearlove

We worked a while ago on a book about the business turnaround of the Olympic Games. It prompted us to look into the evolution of the modern Olympic movement and to pay a visit to the Olympic Museum in Lausanne.

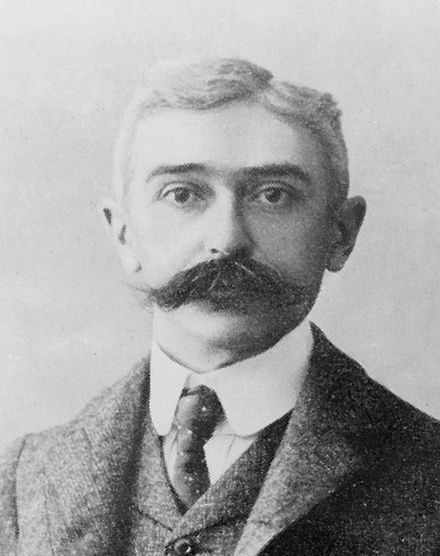

In the late nineteenth century things moved at a more sedentary pace. As a result, the story behind the creation of the modern Olympic Games has a lengthy period of gestation. It was in 1889 that the first important decision in a trail of decisions was made when the French government commissioned Pierre de Coubertin to report on the nation’s physical fitness and methods used to promote what it called ‘physical culture’.

De Coubertin took three years. He traveled widely and examined how other countries nurtured physical fitness among their people. ‘Everywhere I met discord and civil war had been established between the advocates of this or that form of exercise; this state of affairs seemed to e to be the result of an excessive specialization,’ he said. ‘The gymnasts showed bad will towards the rowers, the fencers towards the cyclists, the rifle marksmen towards the lawn-tennis players; peace did not even reign among the adepts of the same sports; the supporters of German gymnastics denied all merit to the Swedish and the rules of American football seemed to the English players not to make common sense.’ Eventually he returned to present his findings at the Sorbonne on 25 November 1892. In his lecture, de Coubertin recommended that international sports competitions be held periodically. The germ of an idea was planted. It was then left.

It reached the next stage in its life when de Coubertin convened an international conference in Paris. Here, he suggested that a modern version of Ancient Greece’s Olympic Games be created. It was decided that the event be held every four years. The conference attracted attendees from twelve countries and twenty-one other nations expressed an interest. A groundswell was emerging.

The conference led to the creation of the International Olympic Committee with de Coubertin as General Secretary. In laying down the rules of the modern Olympics, the Committee made a number of important decisions. They decided that participants would compete regardless of race, color, creed, class or politics and that there would be no financial prizes. ‘Olympism is not a system, it is a state of mind that can permeate a wide variety of modes of expression and no single race or era can claim a monopoly of it,’ said de Coubertin.

In 1896 the first modern Olympic Games were held in Athens – the ancient city had offered to be a permanent home for the Games, but the Committee, and de Coubertin particularly, advocated that the Olympic Games be hosted by a different nation on each occasion. Forty thousand people came to watch the opening ceremony on 6 April 1896. De Coubertin expressed his hope that ‘my idea will unite all in an athletic brotherhood, in a peaceful event whose impact will, I hope be of great significance’.

What does this story offer for the modern leader? First, state your values upfront. The Olympic ideal is based on simple values and precepts which were stated at the very start of the movement. They have lasted.

De Coubertin moved from having a vision to reality. Visions can become reality. Really.

And then there is his Olympian persistence. Pierre de Coubertin’s heart is buried at Olympia. His epitaph reads:

‘The main issue in life is not the victory but the fight. The essential is not to have won but to have fought well.’ The genesis of the Olympic Games was slow, but de Coubertin stuck with his vision which still lives on.

The business side of the Olympic Games is excellently told in the book we mention, Olympic Turnaround by Michael Payne.

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| LANG | 9 hours | Linkedin set this cookie to set user's preferred language. |

| nsid | session | This cookie is set by the provider PayPal to enable the PayPal payment service in the website. |

| sp_landing | 1 day | The sp_landing is set by Spotify to implement audio content from Spotify on the website and also registers information on user interaction related to the audio content. |

| sp_t | 1 year | The sp_t cookie is set by Spotify to implement audio content from Spotify on the website and also registers information on user interaction related to the audio content. |

| tsrce | 3 days | PayPal sets this cookie to enable the PayPal payment service in the website. |

| x-pp-s | session | PayPal sets this cookie to process payments on the site. |

| __cf_bm | 30 minutes | This cookie, set by Cloudflare, is used to support Cloudflare Bot Management. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| l7_az | 30 minutes | This cookie is necessary for the PayPal login-function on the website. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| CONSENT | 2 years | YouTube sets this cookie via embedded youtube-videos and registers anonymous statistical data. |

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_10408481_1 | 1 minute | Set by Google to distinguish users. |

| _ga_ZP8HQ8RZXS | 2 years | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| NID | 6 months | NID cookie, set by Google, is used for advertising purposes; to limit the number of times the user sees an ad, to mute unwanted ads, and to measure the effectiveness of ads. |

| test_cookie | 15 minutes | The test_cookie is set by doubleclick.net and is used to determine if the user's browser supports cookies. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |

| yt-remote-connected-devices | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt-remote-device-id | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt.innertube::nextId | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| yt.innertube::requests | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| DEVICE_INFO | 5 months 27 days | No description |

| loglevel | never | No description available. |

| m | 2 years | No description available. |

Thinkers50 Limited has updated its Privacy Policy on 28 March 2024 with several amendments and additions to the previous version, to fully incorporate to the text information required by current applicable date protection regulation. Processing of the personal data of Thinkers50’s customers, potential customers and other stakeholders has not been changed essentially, but the texts have been clarified and amended to give more detailed information of the processing activities.