Virtual Event

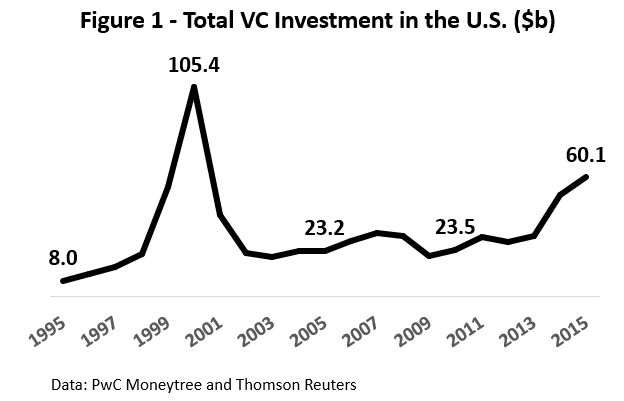

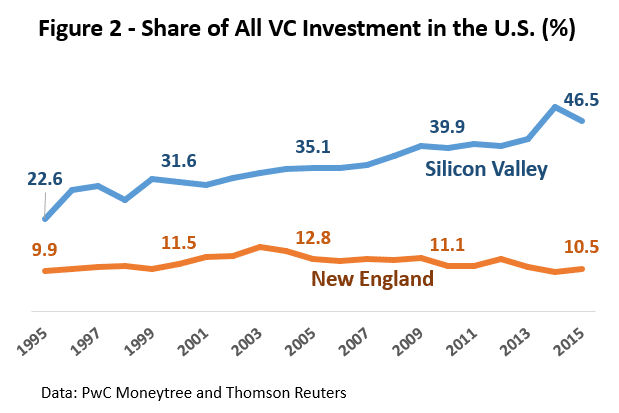

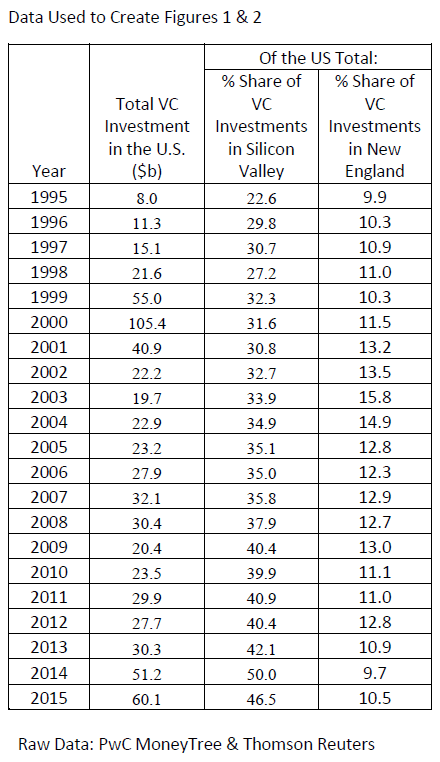

Despite the East Coast roots of technology entrepreneurship and venture capital (VC), it is well documented that, by the 1990s, Silicon Valley had stolen a march on the Cambridge-Boston area. In 1995, Silicon Valley’s share of all VC investments in the U.S. stood at 22.6%, more than twice New England’s share at 9.9%. It is less well-known however that, since then, Silicon Valley’s share of U.S. venture capital has skyrocketed, unaffected by wide fluctuations in the total pool of VC investments during this period. With an almost 50% share, the Bay Area now towers over New England, whose share has stayed put at around 10% (Figures 1 and 2).

The causes behind the initial divergence between the two regions have been amply documented. In her pioneering research on Silicon Valley’s advantage over Route 128 circa 1990, Anna Lee Saxenian identified cultural factors as well as state-level policies as some of the major differentiating factors. Silicon Valley benefited from a more free-wheeling, less hierarchical, and more risk-taking culture than New England. Additionally, unlike Massachusetts, the state of California prohibited non-compete covenants in employment contracts. These policy differences fostered the emergence of a less loyal, more foot-loose talent pool in Silicon Valley. As a result, Bay Area companies were almost always more paranoid and under pressure to run at a faster pace than their East Coast peers.

What factors account for Silicon Valley’s growing divergence from the Cambridge-Boston area during the last twenty years? We propose three mutually reinforcing hypotheses.

First, digital transformation is rapidly engulfing almost all industries. The transformation which started from retailing, music, and movies in the 1990s has now spread to education, financial services, autos and trucks, transportation services, energy and environment, hotels and lodging, life sciences, all types of manufacturing, and even shipping, to name just a few. The underlying technologies (e.g., sensors, search, social media, and artificial intelligence) cut across all of these industries.

Silicon Valley dominates these platform technologies. This is why, given a choice, a growing number of technology entrepreneurs prefer to launch their ventures in – or, as in the case of Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, migrate to – Silicon Valley. This is also why Silicon Valley has become the go-to place for the digital labs of companies from a diverse array of “traditional” industries (such as GE, Walmart, Goldman Sachs, Daimler-Benz, and the like). Physical proximity to technology creators, cutting-edge engineering talent, complementors, and even competitors matters. The result is a growing agglomeration effect in Silicon Valley.

Second, as the LinkedIn cofounder Reid Hoffman has persuasively argued, Silicon Valley has developed a comparative advantage in the art and science of scaling up. Once Silicon Valley surged ahead of New England and other regions in creating and growing new ventures, it found itself with an ever-larger pool of experienced entrepreneurs and senior executives who were ready to start, join, invest in, or otherwise help other new ventures. Witness the career trajectories of the founding team at PayPal which included Elon Musk, Reid Hoffman, Peter Thiel and other now-notable serial entrepreneurs.

Third, as the market for private capital has grown and matured, new ventures can increasingly raise extremely large sums of capital without the necessity of a public listing. Witness the case of Uber, which has a market valuation exceeding $60 billion and is still a privately held company. Given its wider array of startups and an advantage in the art and science of scaling up, Silicon Valley has become a prime beneficiary of this new development in capital markets.

The very same factors that are propelling Silicon Valley’s growing dominance within the U.S. ecosystem are also at play in other major economies. Software hubs are stealing a march over hardware or domain-focused hubs. As a result, tech venturing and VC investments are growing faster in Beijing than in Shanghai or Shenzhen, in Bangalore than in Mumbai or Delhi, and (until the Brexit vote) in London than in Berlin or Paris.

The likely trend in global technology entrepreneurship? We predict that, even as tech venturing and venture capital take deeper roots in regions outside the U.S., we should expect an increasing concentration in a small number of software-centric hubs. As of now, the likely candidates outside the U.S. appear to be Beijing, Bangalore, Tel Aviv, London, and Berlin.

Anil K. Gupta is the Michael Dingman Chair in Strategy, Globalization and Entrepreneurship at the Smith School of Business, The University of Maryland at College Park. Haiyan Wang is Managing Partner, China India Institute, a Washington DC based research and advisory organization. They are the co-authors of The Quest for Global Dominance, Getting China and India Right, and The Silk Road Rediscovered.

Note: A condensed version of this piece appeared in https://hbr.org/2016/11/the-reason-silicon-valley-beat-out-boston-for-vc-dominance

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| LANG | 9 hours | Linkedin set this cookie to set user's preferred language. |

| nsid | session | This cookie is set by the provider PayPal to enable the PayPal payment service in the website. |

| sp_landing | 1 day | The sp_landing is set by Spotify to implement audio content from Spotify on the website and also registers information on user interaction related to the audio content. |

| sp_t | 1 year | The sp_t cookie is set by Spotify to implement audio content from Spotify on the website and also registers information on user interaction related to the audio content. |

| tsrce | 3 days | PayPal sets this cookie to enable the PayPal payment service in the website. |

| x-pp-s | session | PayPal sets this cookie to process payments on the site. |

| __cf_bm | 30 minutes | This cookie, set by Cloudflare, is used to support Cloudflare Bot Management. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| l7_az | 30 minutes | This cookie is necessary for the PayPal login-function on the website. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| CONSENT | 2 years | YouTube sets this cookie via embedded youtube-videos and registers anonymous statistical data. |

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_10408481_1 | 1 minute | Set by Google to distinguish users. |

| _ga_ZP8HQ8RZXS | 2 years | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| NID | 6 months | NID cookie, set by Google, is used for advertising purposes; to limit the number of times the user sees an ad, to mute unwanted ads, and to measure the effectiveness of ads. |

| test_cookie | 15 minutes | The test_cookie is set by doubleclick.net and is used to determine if the user's browser supports cookies. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |

| yt-remote-connected-devices | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt-remote-device-id | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt.innertube::nextId | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| yt.innertube::requests | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| DEVICE_INFO | 5 months 27 days | No description |

| loglevel | never | No description available. |

| m | 2 years | No description available. |

Thinkers50 Limited has updated its Privacy Policy on 28 March 2024 with several amendments and additions to the previous version, to fully incorporate to the text information required by current applicable date protection regulation. Processing of the personal data of Thinkers50’s customers, potential customers and other stakeholders has not been changed essentially, but the texts have been clarified and amended to give more detailed information of the processing activities.