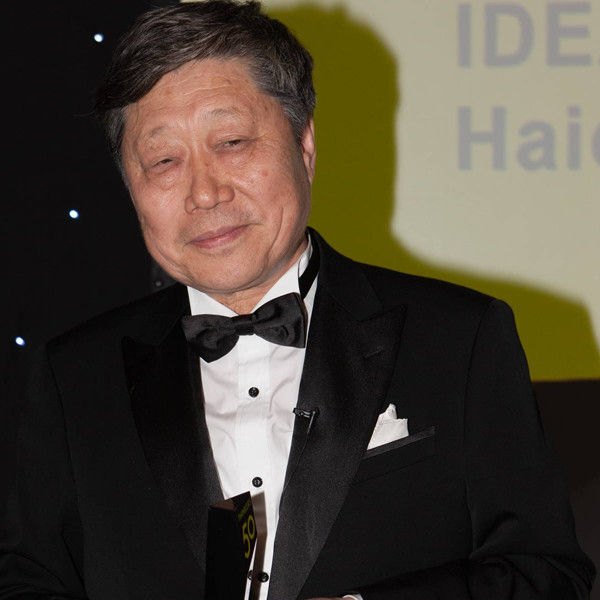

Zhang Ruimin, CEO of Haier, the world’s biggest white goods manufacturer, won the Ideas into Practice Award at Thinkers50 2015. Stuart Crainer examines a new model for organizations and leaders.

Before the Thinkers50 2015 event, myself and Des Dearlove found ourselves in a dining room over a pub in London’s Belgravia. Our guests for the evening were Zhang Ruimin of Haier, his interpreter, and two colleagues. Then for three riveting hours we heard the story of Haier and Zhang Ruimin’s amazing work in reinventing management and organizations for the twenty first century. Along the way what became clear was that we were in the presence of a remarkable man. A leader.

Zhang Ruimin is 66-years old. He has a slightly stooped air of humility, but humility charged with energy. While other business leaders work on emails in airport lounges he is more likely to be found reading a book. Indeed, Zhang Ruimin is the best-read business executive I have ever encountered. His conversation is sprinkled with references to those whose ideas have influenced him – Don Tapscott, Kevin Kelly, Henry Mintzberg by way of Confucius and Lao Tzu.

How Haier became the world’s biggest home appliances maker, the fastest-growing home appliance brand, and one of the largest non-state-owned enterprises in China has entered business legend. The development of Haier is an eye-catching corporate story by any standards. It was in 1984 that Zhang Ruimin took over as Director of the Qingdao Refrigerator Factory. The small collectively-owned factory was losing money. Others had tried to turn the venture around and failed. Money had to be borrowed to pay wages and products often had to be repaired before leaving the factory.

Since then Zhang Ruimin and Haier have cut an impressive swathe through business orthodoxy. Their experiments and innovations in management are unique in their scale.

Usually, management innovations start in smaller organizations and migrate, in slightly diluted form, to their bigger counterparts over time. Despite all the trumpeting of change programs and the like, large organizations tend not to change the way they operate to any significant extent. Change is often decorative tweaking rather than a radical overhaul. Those that do – think ABB in the 1980s – usually end up in retreat, theoretically and commercially.

That Haier has managed to maintain business growth and ground-breaking organizational innovation over a sustained period is unusual and owes a great deal to the leadership of the company. It has succeeded in well-established markets against strong competition. The fact that it is a Chinese company adds piquancy to an already powerful story.

Haier’s success is based on five foundations:

Even though the literature on change is enormous, the managerial and organizational appetite for change tends to be limited. In the same way as turkeys are not inclined to vote for Christmas, leaders of successful organizations are disinclined to change things if they are remotely successful. Few individuals or corporations have managed to change successfully, even fewer have done so repeatedly. Haier has done just that.

During the 1980s, Haier dedicated itself to brand building. Its realization was that to compete internationally it had to raise the standards of its products. Zhang Ruimin proposed the principle of “a late starter with a high starting point”. (To the Western ear, he has an aphoristic and somewhat cryptic turn-of-phrase. Elsewhere, he has observed: “When a storm comes, pigs can also fly in the sky — although they don’t know why.”)

Famously, in 1985, after receiving letters from consumers complaining about quality problems with Haier refrigerators, Zhang joined employees in demolishing 76 of the sub-standard refrigerators with sledgehammers. The point was made: Haier had to match or exceed the highest quality standards.

In the nineties the focus shifted to diversification with a variety of mergers and restructurings. The Haier refrigerator brand was extended to a range of other home appliances – washing machines, air conditioners, microwave ovens, televisions, computers and more.

From there, Haier moved to internationalization with an emphasis on localized R&D, manufacturing and marketing. Its international moves were bold – eschewing easier and closer markets it headed to the United States and Europe where markets were highly competitive and quality expectations high. Following on was Haier’s global brand stage, its acceptance as a powerful brand presence worldwide.

In December 2012 Haier announced its entrance into a fifth development stage: networking strategy. This, Haier explains, aims “to connect the networking market with the networking organization”. “The internet mindset for a business should be a zero distance and networked mindset,” Zhang Ruimin has explained. “The internet has eliminated the physical distance and enabled businesses to become networked. The competitive tension among a company, its employees and its partners should be defused with the aim of building a collaborative, win-win ecosystem.”

The challenge of change is to instigate it from a position of strength. Repeatedly, companies attempt to change things as their performance deteriorates or their market strength evaporates. Not Haier. Indeed, the more successful it has become the greater its apparent appetite for change.

The dynamos of constant change at Haier are small, self-managed teams. There is nothing new in this. Management history features a number of organizations which have used such teams successfully. Lockheed Martin’s “skunk works” teams in the 1940s were based on small groups and the principles of “quick, quiet and quality”. In 1974 Volvo opened its Kalmar car plant which was designed around the idea of small teams rather than endless production lines being used to produce cars. Consulting firms and other professional service firms continue to utilize small teams to work on projects.

The reason why small, self-managed teams are not automatically embraced by the world’s great corporations is simple: they create an organizational mess, a chaotic free-for-all of talent and ideas. This, Haier counters, is the point: innovation and leading edge thinking is not necessarily a tidy business, a ferment of ideas and activity is preferable to rigidity and stagnation. More orderly organizations beg to differ – and have held sway for corporate generations.

At Haier its 80,000 or so employees have been reorganized into over 2,000 self-organizing units. Within the company these independent units are labeled as ZZJYTs (standing for zi zhu jing ying ti).

The divide between employees and non-employees at Haier is becoming increasingly blurred. Indeed, putting a figure on the actual number of people it employs is becoming ever more difficult. In practice, when there is a new project to be worked on several people bid for it and come together as an independent business unit. The unit dissipates after the project is over and everyone goes back into the marketplace. This effectively creates competition within the organization but also fuels entrepreneurship. The person who loses the bid becomes part of the ZZJYT, known in the internal jargon as a “catfish”, nipping at the tail of the winner to ensure the best possible performance.

“If, in the past, the mission of a company was to create customers, today the mission should be to engage customers from end to end. In the past, customer participation wasn’t an end-to-end experience; now it must become one,” Zhang Ruimin has said. Haier talks of moving from “complete obedience to leaders” to “complete obedience to users”.

Haier’s oft-stated belief is that users are more important than managers. “The bosses are not customers, why should the workers listen to them?” asks Zhang Ruimin. Haier aspires to management without bosses. One of Haier’s core values is that “Users are always right while we need to constantly improve ourselves” and its professed future priority is to produce products to meet the personalised demands of consumers.

The results of this are already many and varied. In white goods the only color is no longer white. Haier makes mass customization work. Order a Haier product on the internet and you can specify the color and features. This is then relayed to the factory so that even washing machines are now customized. Zhang Ruimin told us with evident pride of the latest developments in production with the production line being entirely transparent so that customers can watch their machines being made.

Listening to users means that Haier has developed affordable wine fridges and mini fridges build into computer tables for the student market. It has also developed freezers which include ice cream compartments which are slightly warmer so the ice cream is ready to eat. Products are tailored for individual markets. Pakistani users require larger washing machines for their robes rather than the smaller machines preferred by Chinese users. There are even extra durable washing machines with large hoses which can be used for washing vegetables by Chinese farmers.

In the 1990s Tom Peters colorfully observed that “middle managers are cooked geese”. Some geese were longer lived and, as the company developed, a flock of middle managers assembled at Haier. A student of Max Weber, Zhang Ruimin was hardly likely to allow unproductive bureaucracy to flourish. He regularly quotes Lao Tzu’s quip that, “The best leader is one whose existence is barely known by the people”. The role of managers was imaginatively reconfigured and the company recreated as an open marketplace for ideas and talent. The traditional pyramid structure has been all but flattened.

Crucially, this re-invents the role of managers. Haier regards them as entrepreneurs and “makers”. “It’s better to let employees deal with the market rather than rack our brains to deal with and control them,” Zhang Ruimin has observed. Managers are effectively cut loose. Haier talks of its “Win-win Model of Individual-Goal Combination” which means that the objectives of individual employees and the organisation are on the same trajectory.

In practice this means that Haier employees identify an opportunity based on their knowledge of the needs of users and a team is built to develop a product or service to meet the user need. The end result can be a free standing business. “Haier doesn’t offer you a job but offers you the opportunity to create a job,” runs the company’s slogan.

There have already been some 200 “micro-enterprises” established under the Haier umbrella. So far, only 10 per cent have become fully independent and able to draw all their revenues from market-oriented innovations.

The most fully developed business which has spun out of Haier’s entrepreneurialism is Goodaymart, originally its logistics arm. Goodaymart is now ranked among China’s leading brands with a brand value of 14,286 billion yuan. It deliveries cover the home appliance, home furnishings, home improvement and home decoration industries.

In a total of over 2,800 districts and counties across China Goodaymart promises delivery within 24 hours in more than 1,500 of them and delivery within 48 hours in 460.

In this way, Haier is effectively acting as a corporate venture capitalist, incubating and resourcing fledgling business ideas. Once again there is nothing new in this. Corporate venture capital has a long history but it has usually been at a distance from the core of the company, an indulgent extra.

Management is a magpie science, borrowing ideas from psychology, sociology and elsewhere. Haier has proved adept at borrowing ideas and giving them a fresh and distinctive spin of its own. Japanese-style Total Quality Management was absorbed and, later, the Six Sigma management model. Self-managed teams and a focus on users are hardly ground breaking ideas, but wide scale application of the ideas is.

Many of Zhang Ruimin’s pronouncements wouldn’t be out of place coming from a standard big company CEO. He talks of a free market for talent and executive cream rising to the top. But all come laced with a distinctive Chinese cultural nuance. And they now have a track record of working wherever Haier operates.

For example, after acquiring the Japanese company, Sanyo White Goods in 2011, Haier introduced its Win-win Model of Individual-Goal Combination. The seniority-based compensation system deeply rooted in Japanese firms was broken. Instead, the emphasis was on rewarding people according to how much value they created for users. Managers who generated value found themselves promoted rather than sitting around waiting their turn for elevation. Haier turned the loss-making business around within the year.

The end result is that Haier is reinventing the large corporation so that its role is to be as close as possible to customers and to distribute resources while being effectively without a center.

Inspired by the thinking of the Canadian Don Tapscott, among others, Haier regards the company as a platform for other activities, services and products. Zhang Ruimin describes a future Haier as a service-oriented platform of innovative groups and creative individuals with an array of Haier teams offering niche services to customers. In this model the CEO is a co-ordinator rather than a dictator, working with the consent of the self-managed teams.

The corporate net is widening. Haier taps into the needs and aspirations of users. But it has also spread its R&D network to include widespread collaboration with users, academics, designers, competitors and anyone who has a useful insight. “The entire world is our R&D department,” Zhang Ruimin is fond of saying. Haier talks of Communities of Interest, creating dynamic hubs of bright ideas to develop new business models, products and services, as well as brand new businesses.

On receiving the Thinkers50 award Zahng Ruimin was characteristically humble, philosophical and forward looking. Before thanking Haier employees, he said: “This award gives me lots of courage and confidence. There is no final answer in management, only questions.”

Stuart Crainer () is author of The Management Century and co-founder of the Thinkers50.

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| LANG | 9 hours | Linkedin set this cookie to set user's preferred language. |

| nsid | session | This cookie is set by the provider PayPal to enable the PayPal payment service in the website. |

| sp_landing | 1 day | The sp_landing is set by Spotify to implement audio content from Spotify on the website and also registers information on user interaction related to the audio content. |

| sp_t | 1 year | The sp_t cookie is set by Spotify to implement audio content from Spotify on the website and also registers information on user interaction related to the audio content. |

| tsrce | 3 days | PayPal sets this cookie to enable the PayPal payment service in the website. |

| x-pp-s | session | PayPal sets this cookie to process payments on the site. |

| __cf_bm | 30 minutes | This cookie, set by Cloudflare, is used to support Cloudflare Bot Management. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| l7_az | 30 minutes | This cookie is necessary for the PayPal login-function on the website. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| CONSENT | 2 years | YouTube sets this cookie via embedded youtube-videos and registers anonymous statistical data. |

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_10408481_1 | 1 minute | Set by Google to distinguish users. |

| _ga_ZP8HQ8RZXS | 2 years | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| NID | 6 months | NID cookie, set by Google, is used for advertising purposes; to limit the number of times the user sees an ad, to mute unwanted ads, and to measure the effectiveness of ads. |

| test_cookie | 15 minutes | The test_cookie is set by doubleclick.net and is used to determine if the user's browser supports cookies. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |

| yt-remote-connected-devices | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt-remote-device-id | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt.innertube::nextId | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| yt.innertube::requests | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| DEVICE_INFO | 5 months 27 days | No description |

| loglevel | never | No description available. |

| m | 2 years | No description available. |

Thinkers50 Limited has updated its Privacy Policy on 28 March 2024 with several amendments and additions to the previous version, to fully incorporate to the text information required by current applicable date protection regulation. Processing of the personal data of Thinkers50’s customers, potential customers and other stakeholders has not been changed essentially, but the texts have been clarified and amended to give more detailed information of the processing activities.