Jörg Reckhenrich celebrates the maturing of the dot-com generation.

In 1967 the Beatles released “St. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band”. Bored by touring, the Fab Four invented a virtual band and came up with the first concept album. It was a bold statement about the positive spirit of the “Summer of Love”, inspired by eastern philosophical thinking, at a time when everybody was intoning “we are doing it for the better good”. George Harrison strolled around Haight-Ashbury in San Francisco, wrapped in varicoloured clothes, and sang: “A splendid time is guaranteed for all.”

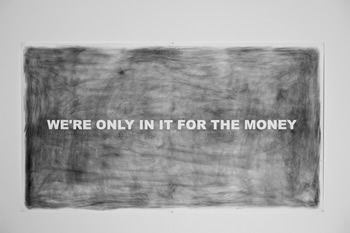

In 1968 Frank Zappa fired back with his album, “We’re Only in it for the Money”, ironically questioning the hippy spirit and taking deliberate lyrical aim at the Beatles. Zappa sang, “I will ask the Chamber of Commerce how to get to Haight Street and smoke an awful lot of dope.” Zappa mistrusted the selfless attitude of the hippies and their lifestyle. He said they took themselves too seriously.

Zappa argued that the whole music movement was turning into a big business. The point was, to Zappa, proved when he called Paul McCartney to ask about rights to the album cover, which is a parody of the famous Beatles cover. McCartney answered that it was an issue for their business managers. Zappa’s responded that the artists themselves are responsible for telling their business managers what to do.

The story marks a turning point in music history. It was when creativity became subsumed by commercial interests, “Super Groups” were born and the music industry grew into a global financial colossus. Groups became brands.

At the heart of this leap is a question which is universal and timeless: what drives organisations?

Fashions change. During the 1980s and 1990s, management theories worked hard at organizational effectiveness, concentrating on financial optimization. Efficiency drove organizations. Then a new spirit was born around the turn of century. Young entrepreneurs came into the business world and played the game differently. Based on ideas, often very vague and sometimes quiet weird, they proudly presented their business concepts to potential financial partners.

The movement created a whole new spirit. Often entrepreneurs proudly claimed to run their businesses for the better good. Pierre Omidyar, who founded eBay in 1995, started the business because he wanted to create an exchange platform for collectibles, his wife’s hobby. The company created a completely different way to look at a market. For many years the organisation and its employees were driven by the vision of rethinking the way that people do business. Among other accomplishments, eBay took the issue of trust, a crucial asset for durable firms, to the next level in the age of the Internet.

In idea-driven companies, such as eBay, employees often work on a level of understanding that life is work and work is life, a claim familiar to artists in the late 1960s, when the poet Emmett Williams said: “Life is art and art is life”. Inspired to turn the world of business into something better, young employees spend hours and hours at work and create an entire private cosmos around themselves. They develop a strong personal relationship towards the company and colleagues, frequently built on pizza delivery service, table football and team activities.

Social coherence was one of the factors that enabled companies to push the boundaries in the dot-com boom. These new organizations used concepts that music bands invented in the late 1960s, when singer-songwriters like Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young sang, “We can change the world.” They brought the spirit to the next level, changed the context, claimed it as the “New Economy”, and business became cool. Established organisations were baffled as these young organizations created an attitude they had always wanted to develop but were not able to, as they were trapped in mechanistic thinking.

The dream, working for the higher purpose of changing the world, ended abruptly when the first dot-com bubble burst in 2001. Too many ideas that had no real business proposition were financed and were not able to create real value. This process educated a whole generation and encouraged people to think about business much more driven by the entrepreneurial spirit. Young entrepreneurs understood the importance of making a difference in the market, by thinking about how to anchor an organization deeper in the needs of society. To convince investors about a business concept, they had to learn this naturally. Numbers were certainly important, but often start-ups got funding, because their idea was perceived as “cool” and unusual. Business became much more than simply making money. The start-up movement claimed that the millions of Euros, which were spent and often burned, was probably one of the most advanced business qualification programs in the post-war years.

Inevitably, the story changed radically after the burst of the dot-com bubble. Daring business concepts were viewed much more sceptically, funding new business ideas was done much more from a clearly financial perspective and it was expected that investments would be paid back within a couple of years.

It seems that the times are once again a-changing. People who started their careers with the beginning of the “new economy”, and have worked for several start-up companies, have already gone — more than once — through the game of funding and selling the organization to multiply the investment. Too often, they saw how organizations lost their soul and work relations were destroyed within weeks. Now they are asking: Are we only in it for the money? There seems to be a new movement starting to rise, and entrepreneurs from the start of the new economy are rethinking the way to run a business. Now they are talking about creating companies around solid business ideas, long-term thinking and developing a workspace for people to spend their time in a meaningful way. Business is becoming more social and more socially aware, but at a more mature level.

Jörg Reckhenrich (www.reckhenrich.com) is a Berlin-based artist and management thinker. He combines unique insights from the art world and his consulting work to further creativity in business contexts. He works as professor of innovation management at Antwerp Management School and is co-author of The Fine Art of Success with Jamie Anderson and Martin Kupp.

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| LANG | 9 hours | Linkedin set this cookie to set user's preferred language. |

| nsid | session | This cookie is set by the provider PayPal to enable the PayPal payment service in the website. |

| sp_landing | 1 day | The sp_landing is set by Spotify to implement audio content from Spotify on the website and also registers information on user interaction related to the audio content. |

| sp_t | 1 year | The sp_t cookie is set by Spotify to implement audio content from Spotify on the website and also registers information on user interaction related to the audio content. |

| tsrce | 3 days | PayPal sets this cookie to enable the PayPal payment service in the website. |

| x-pp-s | session | PayPal sets this cookie to process payments on the site. |

| __cf_bm | 30 minutes | This cookie, set by Cloudflare, is used to support Cloudflare Bot Management. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| l7_az | 30 minutes | This cookie is necessary for the PayPal login-function on the website. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| CONSENT | 2 years | YouTube sets this cookie via embedded youtube-videos and registers anonymous statistical data. |

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_10408481_1 | 1 minute | Set by Google to distinguish users. |

| _ga_ZP8HQ8RZXS | 2 years | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| NID | 6 months | NID cookie, set by Google, is used for advertising purposes; to limit the number of times the user sees an ad, to mute unwanted ads, and to measure the effectiveness of ads. |

| test_cookie | 15 minutes | The test_cookie is set by doubleclick.net and is used to determine if the user's browser supports cookies. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |

| yt-remote-connected-devices | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt-remote-device-id | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt.innertube::nextId | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| yt.innertube::requests | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| DEVICE_INFO | 5 months 27 days | No description |

| loglevel | never | No description available. |

| m | 2 years | No description available. |

Thinkers50 Limited has updated its Privacy Policy on 28 March 2024 with several amendments and additions to the previous version, to fully incorporate to the text information required by current applicable date protection regulation. Processing of the personal data of Thinkers50’s customers, potential customers and other stakeholders has not been changed essentially, but the texts have been clarified and amended to give more detailed information of the processing activities.