It is undeniable that the world around us is changing. Technology and software have transformed large parts of business; and continues to do so in more and more dramatic ways. Corporate leadership would have to be in a special kind of denial to not see how these changes in technology and economics are impacting their businesses. There is no longer the option to keep our heads in the sand. Companies have to respond. What is more challenging now is deciding exactly what companies should do.

And the challenge of how to respond to change is not new. As long ago as 1942, Joseph Schumpeter wrote about Creative Destruction as a process that refreshes economies by injecting new blood in the form of innovative new technologies and companies. But Schumpeter noted that even in the process of creative destruction there is always a chance for companies that would otherwise perish to weather the storm and live on “…vigorously and usefully”. In other words, death is not inevitable. Companies that are able to respond to change, can survive and thrive.

The End of Strategic Advantage

But in order to survive, companies have to become clear eyed about the challenges they are facing. Most traditional MBA teaching has tended to focus on strategy as a method for finding long term competitive advantages. Once these competitive advantages have been found, it becomes the job of managers to devote their energy protecting them. The protection of advantages is done through good financial management and operational excellence. These practices are reasonable in a relatively stable world. But we no longer live there. If ever we did.

Contemporary management thinking recognizes that the ideas of a stable and long term competitive advantage is a fallacy. According to Rita McGrath companies should now be managed to quickly exploit current advantages and move on to the next advantage. This is the perennial problem that has always faced companies, i.e. how to engage in sufficient exploitation to ensure current viability, while devoting enough energy to exploration to ensure future viability (see James March’s work on this). It is the exploration part of the equation that established companies still tend to struggle with.

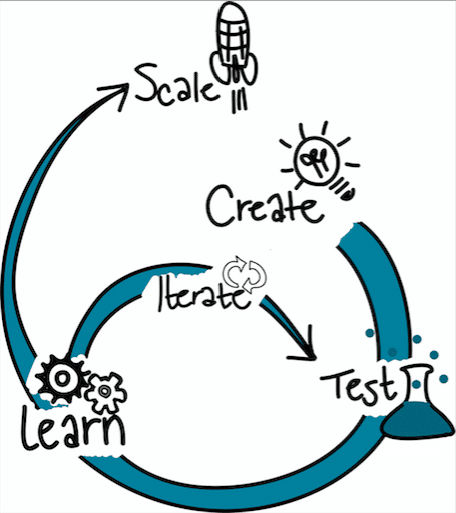

Keep Calm and Do Lean Startup

Nowadays entrepreneurs are rockstars. This has been fueled by the rise of several billion dollar unicorns (e.g. Google, Facebook, Dropbox, Uber); and the apparent demise of several long-standing established companies (e.g. Blockbuster, Nokia, Kodak, Blackberry). The Lean Startup movement’s popularity has triggered the cry that large established companies should be acting like startups. But how does a company that already has a well established cash-cow business act like a startup?

Large companies are not startups, nor should they strive to be. Steve Blank’s distinction between searching and executing is a powerful metaphor for startups to know where they are on their journey. But for established companies the work is in knowing how to search while executing. They also have to be clear that they are not simply searching for cool new ideas. It is the combination of cool new ideas and profitable business models that defines successful innovation.

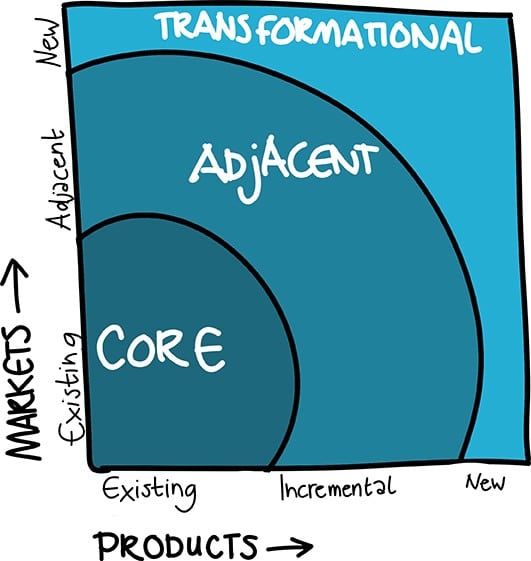

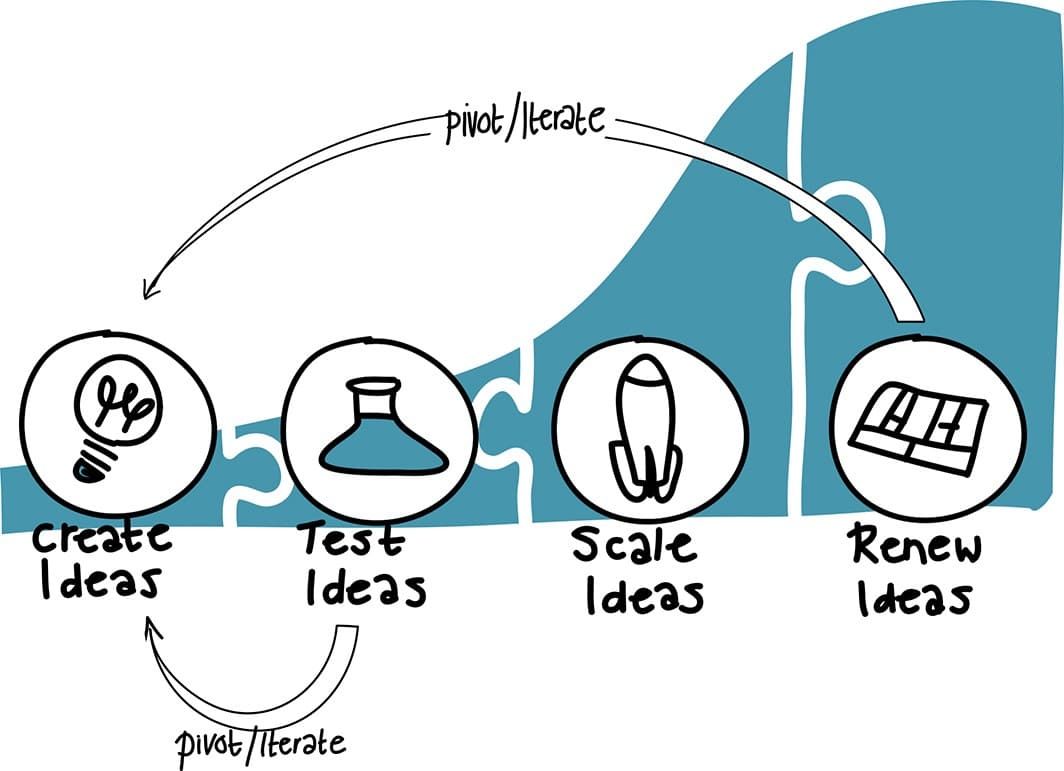

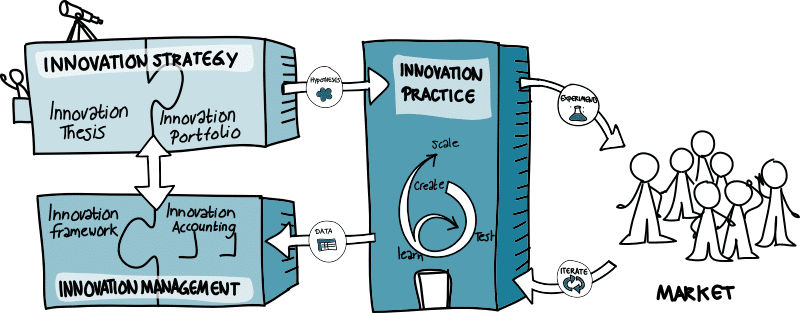

So instead of viewing themselves as single monolithic organizations, established companies have to take an ecosystems approach to their business. Every contemporary company has to be a balanced mix of established products and new products that are searching for profitable business models. The innovation ecosystem and the products within it have to be managed appropriately depending on where they are on their innovation journey (i.e. searching vs. executing).

Our upcoming book, The Corporate Startup, outlines the five core principles that established companies can use to build their innovation ecosystems. These five principles will be briefly described below:

Our book, The Corporate Startup, gets into more details of each principle and how companies can build their innovation ecosystems. Please order it here.

*Special thanks to Esther Gons for the wonderful work she is doing designing the graphics for the book. You can follow her on Twitter.

Originally published on Medium.

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| LANG | 9 hours | Linkedin set this cookie to set user's preferred language. |

| nsid | session | This cookie is set by the provider PayPal to enable the PayPal payment service in the website. |

| sp_landing | 1 day | The sp_landing is set by Spotify to implement audio content from Spotify on the website and also registers information on user interaction related to the audio content. |

| sp_t | 1 year | The sp_t cookie is set by Spotify to implement audio content from Spotify on the website and also registers information on user interaction related to the audio content. |

| tsrce | 3 days | PayPal sets this cookie to enable the PayPal payment service in the website. |

| x-pp-s | session | PayPal sets this cookie to process payments on the site. |

| __cf_bm | 30 minutes | This cookie, set by Cloudflare, is used to support Cloudflare Bot Management. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| l7_az | 30 minutes | This cookie is necessary for the PayPal login-function on the website. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| CONSENT | 2 years | YouTube sets this cookie via embedded youtube-videos and registers anonymous statistical data. |

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_10408481_1 | 1 minute | Set by Google to distinguish users. |

| _ga_ZP8HQ8RZXS | 2 years | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| NID | 6 months | NID cookie, set by Google, is used for advertising purposes; to limit the number of times the user sees an ad, to mute unwanted ads, and to measure the effectiveness of ads. |

| test_cookie | 15 minutes | The test_cookie is set by doubleclick.net and is used to determine if the user's browser supports cookies. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |

| yt-remote-connected-devices | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt-remote-device-id | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt.innertube::nextId | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| yt.innertube::requests | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| DEVICE_INFO | 5 months 27 days | No description |

| loglevel | never | No description available. |

| m | 2 years | No description available. |

Thinkers50 Limited has updated its Privacy Policy on 28 March 2024 with several amendments and additions to the previous version, to fully incorporate to the text information required by current applicable date protection regulation. Processing of the personal data of Thinkers50’s customers, potential customers and other stakeholders has not been changed essentially, but the texts have been clarified and amended to give more detailed information of the processing activities.