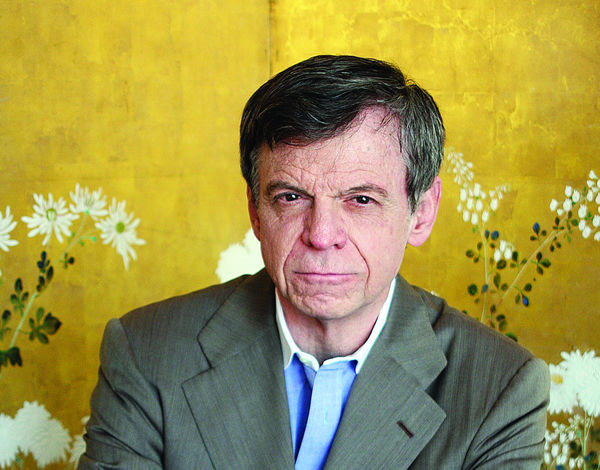

While some of his Harvard Business School colleagues are prolific contributors to the Harvard Business Review, John Kotter has written only six articles. At first sight, it seems a slender basis for an academic career. But, Kotter’s timing has been impeccable. His ideas have struck a chord. Kotter was on the leadership trail at the right time. Then it was change management. Then culture. Then careers. If success was measured in article reprints, Kotter is a success. Then there are his bestselling books, Leading Change, Corporate Culture and Performance, and A Force for Change. Managers feel that he understands them. So much so that one speaker’s bureau quotes Professor Kotter’s speaking fee as starting at $75,000.

And yet, Kotter is the archetypal career academic. He celebrates 30 years at Harvard in 2002 and was among the youngest Harvard faculty members ever given tenure and a full professorship. He talks to us about how he manages to make the right connections with what is happening in the workplace.

How do you work?

The simple logic of my work is that I am a pure field guy. I hang around talking to people. I talk to managers. I sit and watch them. I snoop around, listen to their problems. It’s simple detective work. My work is developed by looking out of the window at what’s going on. It is about seeing patterns. If I’m good at anything it’s pattern analysis and thinking through the implications of those patterns.

What are you working on now?

My last book was a biography of Konosuke Matsushita who no-one, in the United States at least, knew anything about. Some big insights came out of that which I’m still working through. Now I’m working on Leading Change 2 – Leading Change came out in 1996 – which is a more tactical book than its predecessor. It is told in the first person by people struggling through change.

So you have adopted a more personal tone?

Through my speaking I have become more aware of the power of stories. I use stories constantly – 95 percent of what I do is storytelling. It has evolved as I’ve thought about it as a process of education.

What are your stories drawn from?

There’s no-one who has spent more time talking to managers. That’s one reason why my books have won awards. I spend a huge amount of time talking to people.

Is that worth more than theorizing?

Who would write a better book about trees: Someone in the forest or someone in an office?

You have written about change and the importance of a mobilizing, inspiring vision. Is that possible in an environment marked by downsizing?

It is not easy, but it is both possible and necessary. The key is to go beyond the downsizing clichés — talking only of lean and nice. And, carefree statements like “I see a smaller firm in the future” are not a vision that allows people to see a light at the end of the tunnel, that mobilizes people, or that makes them endure sacrifices.

So, what’s your advice?

Be creative, be genuine, and most of all, know why you’re doing what you’re doing. Communicate that and the organization will be stronger. Anything short of this will breed the cynicism that results when we see inconsistencies between what people say and what they do, between talk and practice.

Can a single person ignite true change?

The desire for change may start with one person — the Lee Iacocca, Sam Walton, or Lou Gerstner. But it certainly doesn’t end there. Nobody can provoke great changes alone. There are people that think it is possible, but it is not true. Successful change requires the efforts of a critical mass of key individuals — a group of two to 50 people, depending on the size of the corporation we are considering — in order to move the organization in significantly different directions. If the minimum of critical mass is not reached in the first stages, nothing really important will happen.

Failing to establish a sense of urgency is one of the key mistakes made by change leaders. In Leading Change you discuss seven additional steps in successful change efforts.

That’s right. Beyond establishing a sense of urgency, organizations need to create a powerful, guiding coalition; develop vision and strategy; communicate the change vision; empower broad-based action; celebrate short-term wins; continuously reinvigorate the initiative with new projects and participants; and anchor the change in the corporate culture.

What does this “guiding coalition” look like?

The guiding coalition needs to have four characteristics. First, it needs to have position power. The group needs to consist of a combination of individuals who, if left out of the process, are in positions to block progress. Second, expertise. The group needs a variety of skills, perspectives, experiences, and so forth relative to the project. Third, credibility. When the group announces initiatives will its members have reputations that get the ideas taken seriously? And fourth, leadership. The group needs to be composed of proven leaders. And remember, in all of this the guiding coalition should not be assumed to be composed exclusively of managers. Leadership is found throughout the organization, and it’s leadership you want — not management.

Who needs to be avoided when building this team?

Individuals with large egos — and those I call “snakes.” The bigger the ego, the less space there is for anyone else to think and work. And snakes are individuals who destroy trust. They spread rumors, talk about other group members behind their backs, nod yes in meetings but condemn project ideas as unworkable or short-sighted when talking with colleagues. Trust is critical in successful change efforts, and these two sorts of individuals put trust in jeopardy.

“Communication” seems to crop up in most discussions of organizational effectiveness, and certainly in discussions of effective change. What do you mean when you use the term?

Effectively communicating the change vision is critical to success. This should seem obvious, yet for some reason, executives tend to stop communicating during change, when in actuality they should be communicating more than ever. Effective change communication is both verbal and nonverbal. It includes simplicity, communicating via different types of forums and over various channels, leading by example — which is very important, and two-way communication. Change is stressful for everyone. This is the worst possible time for executives to close themselves off from contact with employees. And this is particularly important if short-term sacrifices are necessary, including firing people.

Who were your mentors?

There were Paul Lawrence and Tony Athos at Harvard, and the social psychologist Ed Schein at MIT. They all took an interest in me. After that, you collect ideas.

Have you ever thought about working for an organization?

It has never crossed my mind for a nano-second.

How about creating an organization?

At most I’ve had one or two employees. I’ve thought about building an organization, but it’s not necessarily what I’m good at doing.

Have you ever thought about working elsewhere? 30 years with one organization is a long time.

If your business is education Boston is not a bad place to be with Harvard, MIT and its various universities.

But you are involved a role in a number of companies.

I’m investing in a company in the e-learning area. E learning is going to be the biggest thing since Guttenberg. It will take wisdom and ideas and make them available to the many. Access to wisdom will go up by a factor of thousands. As an educator I’ve been exploring the possibilities. It’s great fun to watch it develop from its infancy and try to develop your own vision.

You work in a highly competitive field. Who do you see as your competitors?

If you do well at what you do and it makes an impact, you don’t think in competitive terms. Are you happy with your contribution? When you fail to meet your own expectations then you start thinking in terms of competition.

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| LANG | 9 hours | Linkedin set this cookie to set user's preferred language. |

| nsid | session | This cookie is set by the provider PayPal to enable the PayPal payment service in the website. |

| sp_landing | 1 day | The sp_landing is set by Spotify to implement audio content from Spotify on the website and also registers information on user interaction related to the audio content. |

| sp_t | 1 year | The sp_t cookie is set by Spotify to implement audio content from Spotify on the website and also registers information on user interaction related to the audio content. |

| tsrce | 3 days | PayPal sets this cookie to enable the PayPal payment service in the website. |

| x-pp-s | session | PayPal sets this cookie to process payments on the site. |

| __cf_bm | 30 minutes | This cookie, set by Cloudflare, is used to support Cloudflare Bot Management. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| l7_az | 30 minutes | This cookie is necessary for the PayPal login-function on the website. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| CONSENT | 2 years | YouTube sets this cookie via embedded youtube-videos and registers anonymous statistical data. |

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_10408481_1 | 1 minute | Set by Google to distinguish users. |

| _ga_ZP8HQ8RZXS | 2 years | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| NID | 6 months | NID cookie, set by Google, is used for advertising purposes; to limit the number of times the user sees an ad, to mute unwanted ads, and to measure the effectiveness of ads. |

| test_cookie | 15 minutes | The test_cookie is set by doubleclick.net and is used to determine if the user's browser supports cookies. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |

| yt-remote-connected-devices | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt-remote-device-id | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt.innertube::nextId | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| yt.innertube::requests | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| DEVICE_INFO | 5 months 27 days | No description |

| loglevel | never | No description available. |

| m | 2 years | No description available. |

Thinkers50 Limited has updated its Privacy Policy on 28 March 2024 with several amendments and additions to the previous version, to fully incorporate to the text information required by current applicable date protection regulation. Processing of the personal data of Thinkers50’s customers, potential customers and other stakeholders has not been changed essentially, but the texts have been clarified and amended to give more detailed information of the processing activities.