Virtual Event

If you ask people what’s wrong with their organisation, within minutes sheets of flipchart paper are completed and Blu-Tacked all over the walls. And if you return to these questions a year later, or two years later, people are equally quick to respond. Have you noticed that if you compare what’s written on the flip charts from one year to the next, it is hard to know which list came from which year — nothing or very little, seems to have changed.

This observation led us to ask the question, why when people clearly have ideas about what is wrong and how things could be better is so little progress made? Is it because organisations lack the methods and frameworks for executing change? As consultants, we work with many organisations most of which have for years been adhering to a range of change management and execution methodologies, PRINCE, agile working, etc. And yet this phenomenon persists.

So, we asked ourselves a different question. Are there some people who take their frustrations with how things are and make the change they seek a reality? We interviewed a number of Brookings Scholars — people who through their life’s work have brought about positive change. We interviewed several others from our wider network, who had also made significant positive change. We came to call these people Maverick leaders — Maverick because of their independent thinking and leader because they were able to engage others to make positive change happen. Through the interviews we identify eight characteristics that they all seemed to share. This led us to ask the question, to what extent does the general organisational leadership community share these characteristics?

What we found was, while one of the characteristics was true of our Maverick leader group and the general leadership community — the belief that things could be and should be better — there were four characteristics that significantly differentiated our Maverick leaders from the rest:

Samar Osama spent her youth between Saudi Arabia & Egypt and now lives in Dubai. She is an ordinary woman who takes pleasure in ordinary things. But Samar has never conformed to the expectations of others. With a passion for the application of science to providing quality solutions to health and well-being, Samar found herself at the age of 22 working in a pharmaceutical manufacturing plant responsible for quality control. Her colleagues were almost entirely men and were not about to take instructions from a woman on how they should operate ‘their’ machines. They refused to give her any space in the office area such that she conducted her report writing sitting on the factory stairs.

One evening she cleared a corner in the office, found herself a desk and set up her equipment and notebooks. The men laughed at her, but she stayed put. Six months later, through determination, focusing not on the barriers and the hostility, but by connecting with her colleagues as people, showing an interest in them, and showing them that what she wanted and what they wanted was mutually supportive, she achieved a mindset shift in her colleagues. She also learnt an important lesson. If you want to break the status quo you have to find a way of connecting with and earning the respect of those who are comfortable in the status quo.

No methodology brought about this change, Samar made it happen through trial and error. And why was it so important? Because Samar was breaking the mould in establishing the acceptance for women to work in what was a male preserve in the factory in which she worked. It was not just about the desk, it was about getting the respect and acceptance of her male colleagues, and that meant changing their mindset. Samar is a Maverick leader.

Khadim Hussein was born in a remote village in northern Pakistan. As a child he contracted polio and lost the use of his legs. His friends took him to school in a wheelbarrow. Khadim took it upon himself and with the help of his friends, knocked on the doors of the houses in the village to persuade parents to send their young girls to school. The village elders were against him, his own father was against him.

On the face of it, Khadim had far fewer resources at his disposal than many of those around him. But he had friends, he had a wheelbarrow, and he had a mindset which was, I will find out what it takes, and I will do what it takes. Today the schools Khadim has created have educated thousands of girls. Khadim is a Maverick leader.

It’s not a failure of change methodologies that leads to the inertia in so many organisations; is not a failure of ambition from individuals; it is a lack of Maverick leadership. Is this inevitable, or can anyone become a Maverick leader? In the research for our book, Mavericks: How Bold Leadership Changes the World, our conclusion is we are born with a Maverick spirit which can be reignited at any point in our lives. Any of us can develop and practice the mindset and skill set of a Maverick leader.

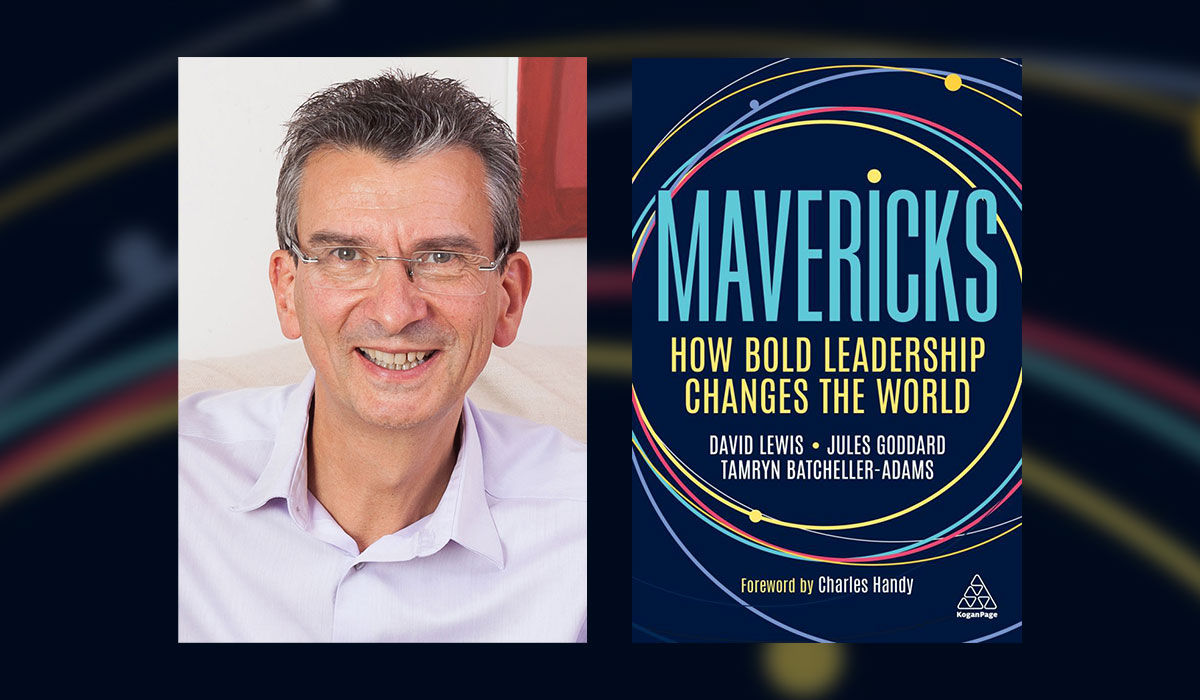

David Lewis is a global business consultant and guest lecturer at the London Business School and Hult International Business School. He is the co-author of Mavericks: How Bold Leadership Changes the World, published by Kogan Page £19.99.

David Lewis is a global business consultant and guest lecturer at the London Business School and Hult International Business School. He is the co-author of Mavericks: How Bold Leadership Changes the World, published by Kogan Page £19.99.

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| LANG | 9 hours | Linkedin set this cookie to set user's preferred language. |

| nsid | session | This cookie is set by the provider PayPal to enable the PayPal payment service in the website. |

| sp_landing | 1 day | The sp_landing is set by Spotify to implement audio content from Spotify on the website and also registers information on user interaction related to the audio content. |

| sp_t | 1 year | The sp_t cookie is set by Spotify to implement audio content from Spotify on the website and also registers information on user interaction related to the audio content. |

| tsrce | 3 days | PayPal sets this cookie to enable the PayPal payment service in the website. |

| x-pp-s | session | PayPal sets this cookie to process payments on the site. |

| __cf_bm | 30 minutes | This cookie, set by Cloudflare, is used to support Cloudflare Bot Management. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| l7_az | 30 minutes | This cookie is necessary for the PayPal login-function on the website. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| CONSENT | 2 years | YouTube sets this cookie via embedded youtube-videos and registers anonymous statistical data. |

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_10408481_1 | 1 minute | Set by Google to distinguish users. |

| _ga_ZP8HQ8RZXS | 2 years | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| NID | 6 months | NID cookie, set by Google, is used for advertising purposes; to limit the number of times the user sees an ad, to mute unwanted ads, and to measure the effectiveness of ads. |

| test_cookie | 15 minutes | The test_cookie is set by doubleclick.net and is used to determine if the user's browser supports cookies. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |

| yt-remote-connected-devices | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt-remote-device-id | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt.innertube::nextId | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| yt.innertube::requests | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| DEVICE_INFO | 5 months 27 days | No description |

| loglevel | never | No description available. |

| m | 2 years | No description available. |

Thinkers50 Limited has updated its Privacy Policy on 28 March 2024 with several amendments and additions to the previous version, to fully incorporate to the text information required by current applicable date protection regulation. Processing of the personal data of Thinkers50’s customers, potential customers and other stakeholders has not been changed essentially, but the texts have been clarified and amended to give more detailed information of the processing activities.