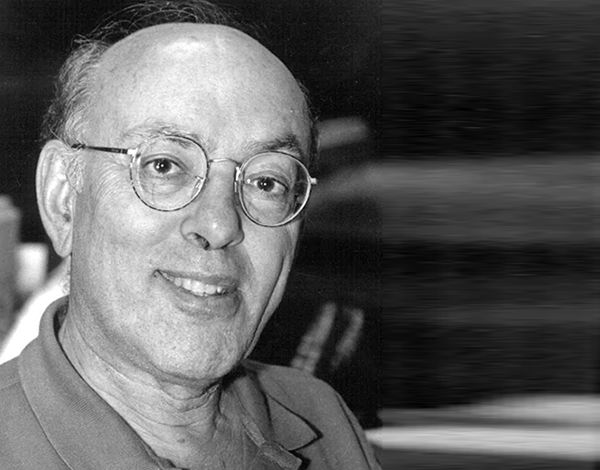

To celebrate Henry Mintzberg receiving the Thinkers50 Lifetime Achievement Award we re-visit our 2001 interview with him.

While most academics focus on how business should work, Henry Mintzberg has focused on how managers really work. His first book, The Nature of Managerial Work, was published in 1973 after being rejected by 15 publishers, and it has become a classic in the field.

Mintzberg has also been a thorn in the side of traditional management education. What was radical 30 years ago is today coming into fashion. Traditional MBA programs around the world are starting to adapt some of the radical ideas and methods of the International Masters in Practicing Management (IMPM) program which Mintzberg helped create. While traditional MBA programs stress learning about business, the IMPM program helps students learn how to manage — recognizing that students have as much to learn from each other as from the faculty.

Always ready with a different perspective on the work of management, his books include Strategy Safari: A Guided Tour Through the Wilds of Strategic Management and Why I Hate Flying: Tales for the Tormented Traveler. To learn more about Mintzberg, visit https://www.henrymintzberg.com.

In this interview from 2001, Mintzberg focuses on his iconoclastic views on strategy and other key management subjects….

You have been critical of formulaic, analysis-driven strategic planning. Why?

Because analysis-driven strategic planning is little more than elaborating and operationalizing the strategies that companies already have. That’s not strategic thinking.

Why does the method fail?

Because it is predicated on three fatal pitfalls. First is the assumption that discontinuities can be predicated. They can’t — at least they can’t with any real accuracy. Forecasting techniques are limited by the fact that they tend to assume that the future will resemble the past. There isn’t much that can be more fatal to an organization than that assumption.

The second pitfall?

Planners are detached from the reality of the organization. Planners have traditionally been obsessed with gathering hard data on their industry, markets, and competitors. Soft data — networks of contacts, talking with customers, suppliers, and employees, using intuition and using the grapevine — have all but been ignored. To gain real understanding of an organization’s competitive situation, soft data needs to be dynamically integrated into the strategy process. While hard data may inform the intellect, it is largely soft data that generate wisdom. They may be difficult to “analyze,” but they are indispensable for synthesis, which is the key to strategy making.

And the third?

The assumption that strategy making can be formalized. The left side of the brain has dominated strategy formulation with its emphasis on logic and analysis. Alternatives which do not fit into the pre‑determined structure are ignored. The right side of the brain needs to become part of the process with its emphasis on intuition and creativity. Planning by its very nature defines and preserves categories. Creativity by its very nature creates categories or rearranges established ones. This is why strategic planning can neither provide creativity, nor deal with it when it emerges by other means. The real challenge in crafting strategy lies in detecting the subtle discontinuities that may undermine a business in the future. And for that there is no technique, no program, just a sharp mind in touch with the situation.

If you’re right, then the “golden age” of strategic planning and perhaps reengineering is over. If so, where is management headed?

I don’t like to play that game. Nobody can predict. The world heads in different directions all the time; who knows which one will dominate. It is absolutely wrong to tell managers what is going to happen next.

Fair enough. How about MBA programs? As a long-standing critic, your comments have had important impacts in America and Europe. What is wrong with MBA programs?

MBA programs train the wrong people in the wrong ways for the wrong reasons. The MBAs are B-programs, business based — not A-programs, about administration (meaning management). People think they are being trained as managers. What kind of managers? They learn to talk, not to listen. Management education should be based on experience. Managers cannot be made in vitro.

In your examinations of managerial work, you found that managers did not do what they liked to think they do.

That’s right. I found that instead of spending time contemplating the long‑term, which is what managers often are assumed to be doing, managers were slaves to the moment, moving from task to task with every move dogged by another diversion, another call. The median time spent on any one issue was a mere nine minutes.

So, if managers aren’t continuously pondering the future, what are their roles?

Managers must perform at three broad levels: informational, people, and action — all three both inside and outside their units. That is one demanding job.

We greatly enjoyed your book Why I Hate Flying. Can you tell us more about it?

It is a spoof on management looking at the management practices of airlines and airports from my experience. “Welcome aboard ladies and gentlemen, this is your author scribbling,” is the opening. At the beginning of each chapter there’s a piece on how the airline and airport experience relates to management. For example, it looks at how change management — “Change always comes first” is one of the lines — converts passengers from cattle into sardines; customer service means constantly interrupting passengers as they try to sleep; and customer loyalty means rewarding people so they fly on other airlines.

Whom would you pick as the most influential management thinker?

Peter Drucker had a lot of ideas; he was undoubtedly a great influence. But I would also name Herbert Simon. He is not very much talked about among the management community, but he had a deep influence on the issue of how the decisions of the manager are made. He changed the way of looking at organizations. In an historic perspective, I would name Frederick Taylor as the most influential. We still continue to practice Taylorism on a large scale.

If you go into a company, what is the most important question you ask?

No, I would ask no questions before I see, on the ground, with my own eyes, what is going on in the place — what it looks like, how it seems to work, who its people are, etc. I have done this often in consulting, and it has proved invaluable.

What questions would you like to ask the managers of the world?

Are you making the world a better place? Do the people who report to you think so?

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| LANG | 9 hours | Linkedin set this cookie to set user's preferred language. |

| nsid | session | This cookie is set by the provider PayPal to enable the PayPal payment service in the website. |

| sp_landing | 1 day | The sp_landing is set by Spotify to implement audio content from Spotify on the website and also registers information on user interaction related to the audio content. |

| sp_t | 1 year | The sp_t cookie is set by Spotify to implement audio content from Spotify on the website and also registers information on user interaction related to the audio content. |

| tsrce | 3 days | PayPal sets this cookie to enable the PayPal payment service in the website. |

| x-pp-s | session | PayPal sets this cookie to process payments on the site. |

| __cf_bm | 30 minutes | This cookie, set by Cloudflare, is used to support Cloudflare Bot Management. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| l7_az | 30 minutes | This cookie is necessary for the PayPal login-function on the website. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| CONSENT | 2 years | YouTube sets this cookie via embedded youtube-videos and registers anonymous statistical data. |

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_10408481_1 | 1 minute | Set by Google to distinguish users. |

| _ga_ZP8HQ8RZXS | 2 years | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| NID | 6 months | NID cookie, set by Google, is used for advertising purposes; to limit the number of times the user sees an ad, to mute unwanted ads, and to measure the effectiveness of ads. |

| test_cookie | 15 minutes | The test_cookie is set by doubleclick.net and is used to determine if the user's browser supports cookies. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |

| yt-remote-connected-devices | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt-remote-device-id | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt.innertube::nextId | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| yt.innertube::requests | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| DEVICE_INFO | 5 months 27 days | No description |

| loglevel | never | No description available. |

| m | 2 years | No description available. |

Thinkers50 Limited has updated its Privacy Policy on 28 March 2024 with several amendments and additions to the previous version, to fully incorporate to the text information required by current applicable date protection regulation. Processing of the personal data of Thinkers50’s customers, potential customers and other stakeholders has not been changed essentially, but the texts have been clarified and amended to give more detailed information of the processing activities.