By Nikhilesh Sinha and Satrupa Ghosh

In 2024, we experienced an average temperature 1.6 degrees above pre-industrial levels, which exceeds the terms in the Paris Agreement. Environmental degradation accelerated across every measurable axis, and we are depleting resources faster than they regenerate, concentrating waste in landfills and oceans whilst extracting virgin materials at an unsustainable rate.

Business as usual with the linear take-make-waste economy is a hazard to our collective health and the future of the planet. We need to rethink how we produce and consume. And fast. With many national governments stepping back from global sustainability commitments, and the richest corporations going all-in in the AI race, it may be up to cities and smaller businesses to drive the change. The question is, can they work together?

Cities are where most of us live, work and create, generating four-fifths of global GDP but also 70 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions. Through the centuries, they have fostered institutional innovation, incubating modern finance, as well as universities and public infrastructure. The contemporary challenge is circular transition – engineering a closed loop between production and consumption to eliminate waste.

Some cities are taking this seriously. San Francisco has committed to eliminating municipal waste by 2020, Copenhagen is targeting 60 per cent recycling by 2030, and Amsterdam plans full circularity by 2050. But this shift isn’t limited to the global North. Bogotá, Taipei, Singapore, Manila, and Nairobi are all pursuing ambitious circular economy strategies, suggesting urban sustainability is becoming a global priority.

London was rated the world’s most circular city in 2024, with a plan to hit net zero targets a full decade before the rest of the UK. The city’s ambitions involve rethinking how products are designed, produced and used. Along with food, plastics, electricals and the built environment, the City’s Circular Routemap has committed to transforming the textile sector. One of the fashion capitals of the world, London’s love affair with fashion comes at a steep cost. Its textile consumption produces over 2 million tonnes of greenhouse gas annually, amounting to about 17 per cent of all emissions linked to the consumption of goods within the city.

In response, a new generation of circular entrepreneurs have picked up the gauntlet, challenging the fast fashion model that offers profits at the cost of planet. Born-circular fashion businesses from clothing swap platforms and repair services, to rental models that make designer wear accessible without ownership, embody the circular principles London champions: keeping materials in use, designing out waste, and regenerating natural systems. While legacy brands have launched circular initiatives like Patagonia’s Worn Wear, Levi’s SecondHand, and Burberry’s ReBurberry, these programmes represent a fraction of their overall revenue and operations.

Circular businesses in London should logically piggyback on the city’s circular initiatives to enhance their circularity and scale. Yet most local circular startups operate in silos, building parallel networks rather than seamlessly connecting with London’s circular systems. The city’s ambitious circular economy plans appear to be blind to the synergies that could be leveraged through coordination with and incorporation of enterprise-level circular flows.

Why is this, and how can we bridge the divide between the circular business and the city? The trouble is that circularity at the city and enterprise scales is not synonymous. Most circular economy thinking was developed for businesses, not cities. Influential frameworks like the Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s ReSOLVE principles focus on what individual companies can do: optimise their operations, close loops between suppliers and consumers, and design out waste within their supply chains.

These work well at the enterprise level, but cities operate fundamentally differently. Circular businesses create closed loops within their operations, whereas circular cities need to optimise across entire urban ecosystems. The urban circular loop is more complex, coordinating across many different functions and actors in ways that individual enterprises need not.

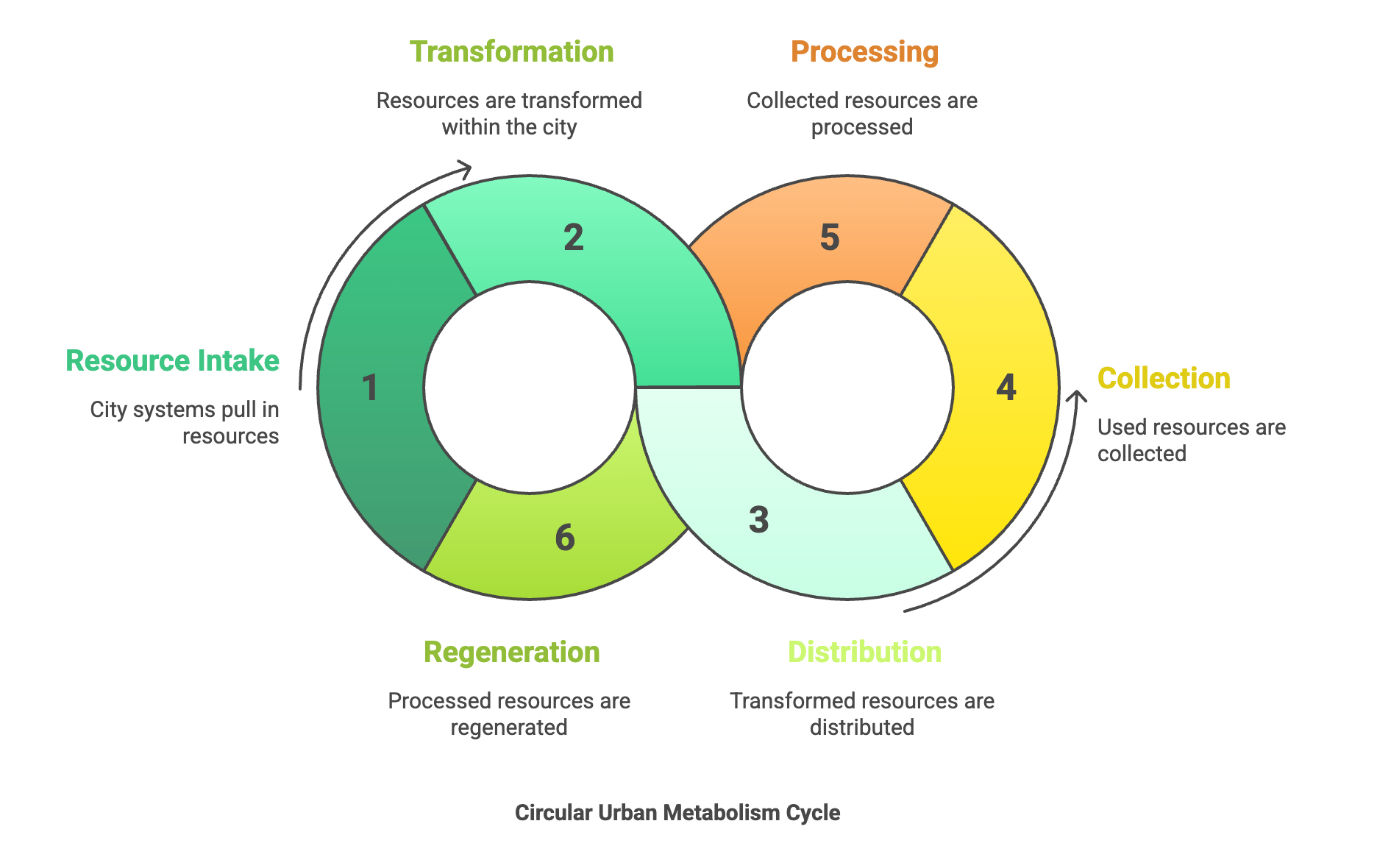

One way to think about this is to imagine the city as a giant organism, with all of the city systems resembling metabolic flows, pulling in resources, transforming and distributing them throughout the city. In a circular metabolism, the flows would constitute closed loops, like blood vessels supplying oxygenated blood, and then looping back to the lungs for replenishment.

For this to work, we need more “connective tissue” of shared infrastructure, coordinated policies, and governance frameworks that allow individual innovations to plug into wider urban resource flows. A repair shop can’t create circular impact without a collection infrastructure to gather materials or sorting facilities to process them. A rental platform multiplies its impact when connected to local repair services and textile recyclers who supply designers with regenerated materials.

To understand the blockages in London’s metabolic flows, we looked at three circular fashion startups, each pioneering a different circular strategy: Closwap operates a peer-to-peer clothing swap platform through a digital marketplace and community events. Circular Way and Stilbaar have created what they call “the world’s first fully circular fashion store,” buying back all of the clothes sold and either refurbishing them or sending them to textile-to-textile recyclers like Evrnu or Circ. HURR offers a full-stack rental solution, facilitating both peer-to-peer rentals and providing turnkey enterprise solutions for brands like Selfridges, and has reportedly surpassed £100 million in fashion rentals since launching in 2019.

Closwap’s gamified platform reduces CO2 emissions by approximately half compared to buying new, while matching “the three Ps of fast fashion: Price, Practicality, and Pace,” as co-founder Maria Remy puts it. Circular Way uses chip technology to track each garment’s lifecycle, enabling customers to transfer the market value of end-of-use garments toward new purchases – what CEO John Atcheson calls a “frictionless” circular shopping experience. HURR’s hybrid model handles the logistical complexity of returns, cleaning, repairs, and customer support. These businesses make circular fashion workable in practice, recovering value, organizing logistics and tracking garments through successive uses.

Yet despite operating in the world’s top-ranked circular city, all three share the troubling reality of scale and impact. Closwap’s community swaps remain neighbourhood-level events. Circular Way contends with borough-level regulatory variations and fragmented infrastructure. HURR operates outside Extended Producer Responsibility frameworks, with no targeted incentives or tailored regulations for rental models.

The city offers patchy support through initiatives such as the Pan-London Textiles Action Plan, the annual London Repair Week engaging 40 organizations, and grants from the Mayor’s office. But as Remy told us, “We can prototype a feature in weeks, but securing city support for a borough-wide collection pilot takes years.” Meanwhile, Fashion Director Sandrine Kockum’s goal to “buy back 100% of the clothes we sell” confronts a reality where there’s no infrastructure connecting repair businesses to collection systems to textile recyclers. And Victoria Prew’s vision to reinvent ownership “one rental at a time” scales primarily in affluent, well-connected neighbourhoods because that’s where courier infrastructure and cleaning services cluster.

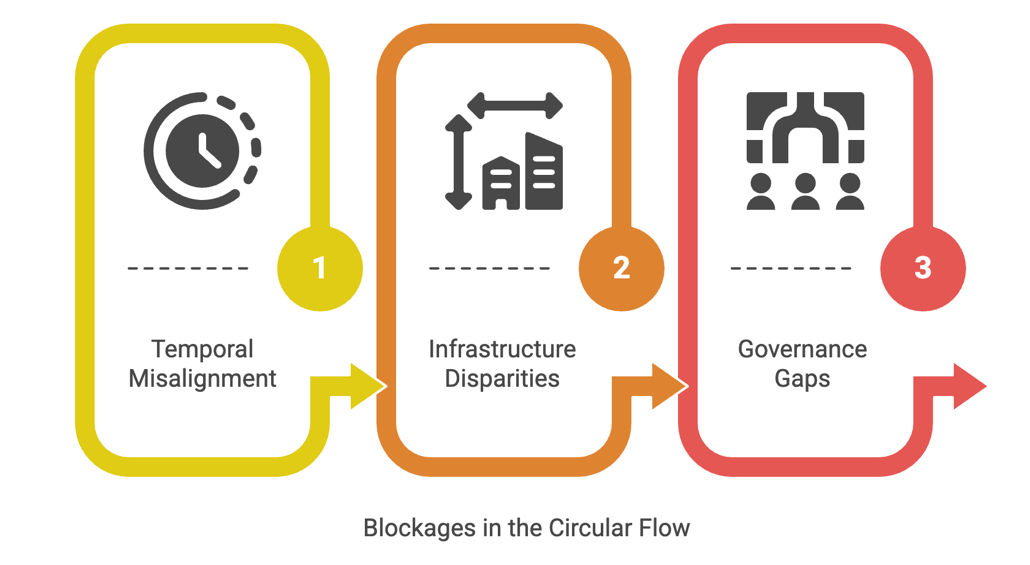

Ambitious as they are, for a city that amasses 82,100 tons of second-hand clothing annually, these startups handle only a fraction of its annual textile flows. Two-thirds of the used clothing collected is ultimately exported overseas, resulting in an opportunity loss where materials that could generate local value instead enter global waste streams. This pattern reflects three structural misalignments between entrepreneurial operations and urban governance, emblematic of the gap between micro-innovation and macro-system inertia.

Temporal Misalignment: Circular enterprises operate on compressed timeframes of quarterly sprints, weekly inventory adjustments, and 24-hour delivery cycles. This tempo mirrors fast-fashion convenience while building sustainable alternatives. London operates on five-year strategic plans, annual budgets, and multi-year waste contracts. This cadence clash forces startups to maintain independent logistics rather than integrate with municipal systems.

Infrastructural Disparities: Startups build their own parallel mini-system because standardised collection points, shared sorting facilities, and coordinated repair hubs don’t exist across London’s 32 boroughs. Services concentrate in affluent, well-connected neighbourhoods, reinforcing socioeconomic disparities.

Governance Gaps: Despite symbolic support, these businesses navigate systems designed for linear consumption. UK VAT applies a 20% rate to repairs, making fixes more expensive than replacements. Extended Producer Responsibility focuses on manufacturers, not circular intermediaries. HURR operates outside EPR frameworks. Closwap’s £5 event tickets can’t offset unsupported costs. Circular Way faces different regulations in each borough, with no repair-specific training programs available.

These divergences create “micro-metabolisms” or circular systems adjacent to rather than integrated with urban metabolism. If the world’s leading circular city can’t bridge this gap, it signals fundamental challenges for circular transitions everywhere.

The circular startups we spoke with show what is possible at the level of individual garments and users. They connect design, use, repair and recovery in ways that echo a functioning metabolism. But they also operate within systems whose scale and tempo were never designed for the small, fast loops these models rely on.

That misalignment limits how far circular startups can push without support. For now, the most practical route for entrepreneurs is to build models that align with infrastructure that does exist: courier networks, community repair groups, borough-level pilots, and textile recyclers design their operations so they can plug into shared systems as they develop. That means treating integration not as a final step once scale is reached, but as a design principle from the outset.

For cities, declaring circular ambitions isn’t enough. What circular cities such as Copenhagen and Amsterdam are doing differently is that they’re not just setting emissions targets. They’re redesigning urban material flows. Copenhagen’s waste ambition isn’t about disposal reduction; it’s about rethinking what “waste” means in the system. That’s metabolic redesign, not just greening the existing model. London’s circular kudos masks a fundamental struggle to build the enabling infrastructure emerging circular businesses need. This means creating shared physical systems, standardised infrastructure across all boroughs, sorting facilities accessible to multiple businesses, resources and repair hubs integrated with transit networks.

The opportunity is substantial. Along with the health benefits of lowering carbon emissions and mitigating the loss of productive land, the World Economic Forum estimates a $1 trillion global annual benefit from circular transition. Localised material loops reduce transportation costs, provide predictable feedstock for manufacturers, generate employment in repair and recovery, and insulate cities from volatile global supply chains. For businesses, integration means access to reliable materials, shared logistics networks, and regulatory clarity. The question isn’t whether circular cities are viable. It’s whether we build the connective tissue quickly enough to capture the value.

Nikhilesh Sinha is Professor of Economics & Finance and Chair of Research Ethics at Hult International Business School. His research in institutional economics, political economy, and urban development has influenced housing policy in India and contributes to debates on circular economy transitions and technology’s impact on governance.

Dr Satrupa Ghosh is Professor of Innovation, Marketing and Entrepreneurship at Hult International Business School. Her research examines venture ecosystems, open innovation models, corporate startup value creation, and sustainability and circularity in regional contexts. She brings a scholar-practitioner perspective, with 20 years’ experience in venture capital and marketing.

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| LANG | 9 hours | Linkedin set this cookie to set user's preferred language. |

| nsid | session | This cookie is set by the provider PayPal to enable the PayPal payment service in the website. |

| sp_landing | 1 day | The sp_landing is set by Spotify to implement audio content from Spotify on the website and also registers information on user interaction related to the audio content. |

| sp_t | 1 year | The sp_t cookie is set by Spotify to implement audio content from Spotify on the website and also registers information on user interaction related to the audio content. |

| tsrce | 3 days | PayPal sets this cookie to enable the PayPal payment service in the website. |

| x-pp-s | session | PayPal sets this cookie to process payments on the site. |

| __cf_bm | 30 minutes | This cookie, set by Cloudflare, is used to support Cloudflare Bot Management. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| l7_az | 30 minutes | This cookie is necessary for the PayPal login-function on the website. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| CONSENT | 2 years | YouTube sets this cookie via embedded youtube-videos and registers anonymous statistical data. |

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_10408481_1 | 1 minute | Set by Google to distinguish users. |

| _ga_ZP8HQ8RZXS | 2 years | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| NID | 6 months | NID cookie, set by Google, is used for advertising purposes; to limit the number of times the user sees an ad, to mute unwanted ads, and to measure the effectiveness of ads. |

| test_cookie | 15 minutes | The test_cookie is set by doubleclick.net and is used to determine if the user's browser supports cookies. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |

| yt-remote-connected-devices | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt-remote-device-id | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt.innertube::nextId | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| yt.innertube::requests | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| DEVICE_INFO | 5 months 27 days | No description |

| loglevel | never | No description available. |

| m | 2 years | No description available. |

Thinkers50 Limited has updated its Privacy Policy on 28 March 2024 with several amendments and additions to the previous version, to fully incorporate to the text information required by current applicable date protection regulation. Processing of the personal data of Thinkers50’s customers, potential customers and other stakeholders has not been changed essentially, but the texts have been clarified and amended to give more detailed information of the processing activities.