One of the most influential ideas in the innovation world of recent years is that of the innovator’s dilemma, the title of a 1997 book by Clay Christensen. When we met Christensen in his Harvard office we asked him to explain the concept. “So the dilemma is that every day and every year in every company, people are going to senior management, knocking on the door, and saying, I’ve got a new product for us. And some of those entail making better products that you could sell for higher prices to your best customers,” he replied. “But a disruptive innovation generally causes you to go after new markets, to reach people who aren’t your customers, and the product that you want to sell them is something that is just so much more affordable and simpler that your current customers can’t buy it. And so the choice that you have to make is, should we make better products that we can sell for better profits to our best customers? Or maybe we ought to make worse products that none of our customers would buy that would ruin our margins? What should we do? And that really is the dilemma.

“It’s the dilemma that General Motors and Ford faced when they tried to decide, should we go down and compete against Toyota, who came in at the bottom of their markets, or should we make even bigger SUVs for even bigger people? And now Toyota has the same problem. The Koreans, with Hyundai and Kia, have really won the low end of the market from Toyota, and it’s not because Toyota’s asleep at the switch. Why would it ever invest to defend the lowest-profit part of its market, which is the subcompacts, when it has the privilege of competing against Mercedes? And now Chery is coming from China, doing the same thing to the Koreans.”

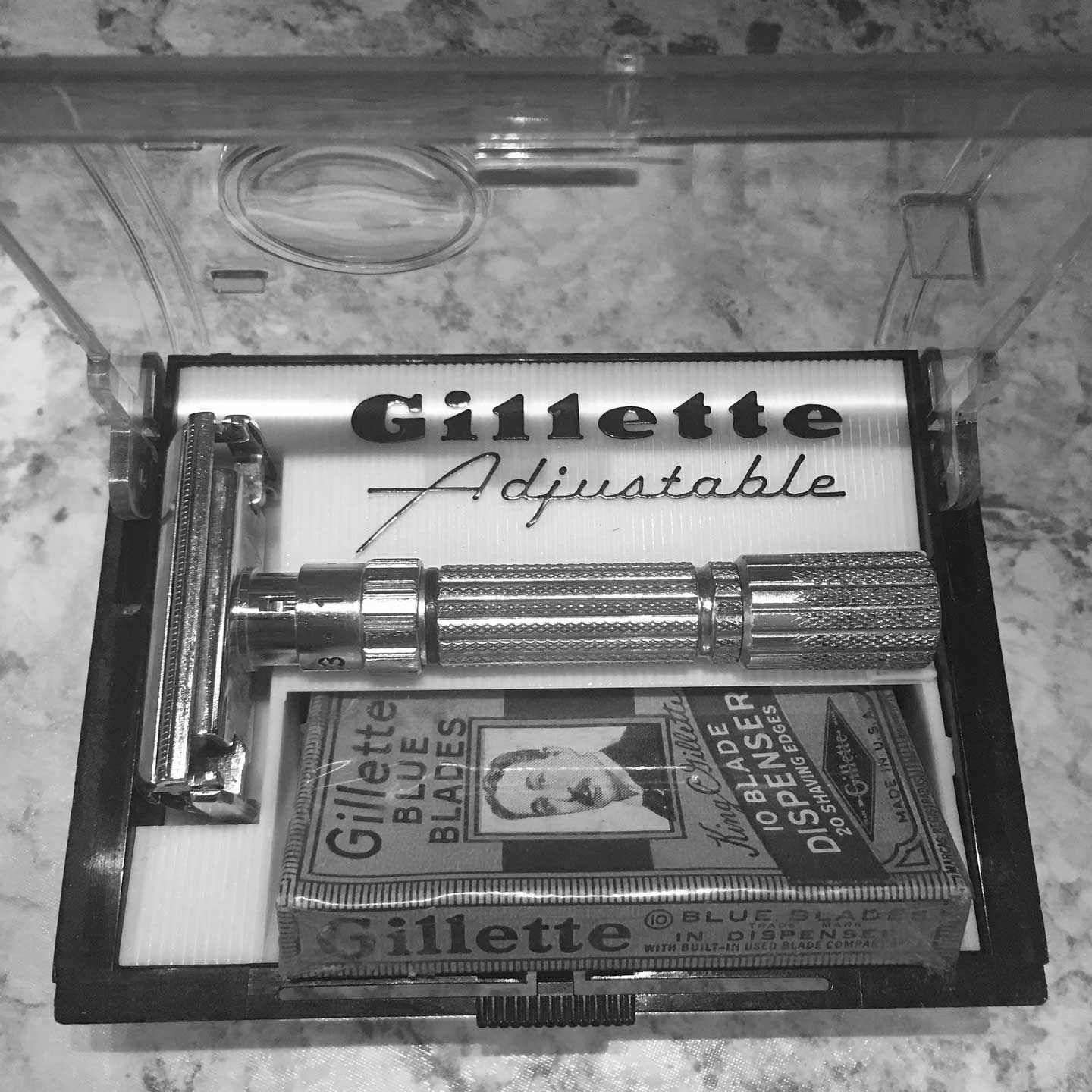

Clay Christensen’s insights took us back to the 1970s when the razor manufacturer Gillette was under threat from all sides. Competition was pushing it downmarket. It cut prices and profits plummeted. Predators waited. Then it made a decision which turned the company around: its place was at the high quality, premium price end of the market. Period.

The reality is that sometimes companies forget what they are good at. They become distracted, take their eye off the ball and usually watch helplessly as profits plummet.

That is exactly what was happening to Gillette in the 1970s. As cheap throwaway razors made their presence felt in its markets, it was pushed relentlessly downmarket. “The critics didn’t understand the real problem. It was that Gillette had lost sight of what its brand was,” observed Bradley Gale of the Strategic Planning Institute. “Marketers can create brand power and superior returns almost anywhere – if they focus on becoming perceived quality leaders.”

Then Gillette realized that quality mattered and that innovation rather than relentless price cutting was the soul of its business. Its great decision, therefore, was to invest in the development of the Sensor range of razor blades. It decided to take its foot off the price-cutting pedal and take time to develop a genuine market-changing product.

This process actually began in 1979, but the Sensor wasn’t introduced until 1990. Gillette spent $275 million on designing and developing the range. Sensor has been one of the great business successes of recent years – by 1995 it accounted for $2.6 billion in sales. With 68 percent of the US wet shaving market and 73 percent of the European market, competitors haven’t made any inroads into Sensor’s domination.

Since then the brand has carved out a lucrative niche for itself in what is labeled male and female grooming as well as in a number of areas, including alkaline batteries. Gillette’s empire now includes Braun electrical appliances; toiletries and cosmetics; stationery products (it owns Parker and Papermate pens); Oral-B toothbrushes and the battery-maker, Duracell with which Gillette merged in 1996. Little wonder that it is estimated that over 1.2 billion people use a Gillette product every day. This explains why the company had 1997 sales of $10.1 billion and has 44,000 employees working in 63 facilities in 26 countries.

Gillette’s fans included Warren Buffett who commented: “I go to bed happy at night, knowing that hair is growing on billions of male faces.” For investors like Buffett, Gillette had a number of attractions. Most notably, Gillette appears to have now struck a balance between innovation and the marketplace. “Good products come out of market research,” said then CEO Alfred Zeien. “Great products come from R&D. And blockbusters are born when something great comes out of the lab at the same time people want it.” Zeien – like Warren Buffett and company founder, King Gillette – takes the long view. He points to similarities between Gillette developing new products and the long-term R&D necessary to develop new drugs.

The lessons from the Gillette story are simple enough. First: Don’t get caught doing what the competition is doing. With stores filling with Bics and other disposable brands, Gillette made the mistake of competing at the same level. It basically sought to out-Bic Bic. It couldn’t. Aping the competition is not a strategy, but a cop out.

Second, think and act global. Gillette is truly global in its reach and operations. Over 70 percent of its sales and profits come from outside the United States. No less an authority than Rosabeth Moss Kanter has said that “Gillette does internationally what every company should be doing”. Gillette can only hope that it continues to be so little emulated.

Third, bright ideas take time. “Invent something people use and throw away,” a wise man told King Camp Gillette (1855-1932) in 1895. Gillette started thinking. Later he thought of a disposable safety razor. Then he met the inventor William Nickerson. The Gillette company started life in 1901 on the Boston waterfront as the Gillette Safety Razor Company with Gillette trying to persuade investors to put their money into a company with an untested product. (The name Nickerson didn’t feature because it suggested nicking yourself shaving.) It was not until 1903 that the company began production of its razor sets and blades.

During its first year, Gillette sold 51 razor sets and 168 blades. By 1905 it was selling 250,000 razor sets and nearly 100,000 blade packages. And, by 1915, sales had increased hugely once more so that the company was selling 7 million blades a year. In 1917 the US government placed an order for 3.5 million razors and 36 million blades. In 1923, Gillette produced a gold plated razor – a snip at a dollar. (By this time King Gillette had disappeared into the sunset – Los Angeles – to convert his experience into social theories.)

The innovator’s dilemma remains perpetually potent. Make your choice.

Resources

Clayton Christensen, The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail, Harvard Business Review Press, 1997.

This was originally published in What we mean when we talk about innovation by Stuart Crainer and Des Dearlove (Infinite Ideas, 2016).

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| LANG | 9 hours | Linkedin set this cookie to set user's preferred language. |

| nsid | session | This cookie is set by the provider PayPal to enable the PayPal payment service in the website. |

| sp_landing | 1 day | The sp_landing is set by Spotify to implement audio content from Spotify on the website and also registers information on user interaction related to the audio content. |

| sp_t | 1 year | The sp_t cookie is set by Spotify to implement audio content from Spotify on the website and also registers information on user interaction related to the audio content. |

| tsrce | 3 days | PayPal sets this cookie to enable the PayPal payment service in the website. |

| x-pp-s | session | PayPal sets this cookie to process payments on the site. |

| __cf_bm | 30 minutes | This cookie, set by Cloudflare, is used to support Cloudflare Bot Management. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| l7_az | 30 minutes | This cookie is necessary for the PayPal login-function on the website. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| CONSENT | 2 years | YouTube sets this cookie via embedded youtube-videos and registers anonymous statistical data. |

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_10408481_1 | 1 minute | Set by Google to distinguish users. |

| _ga_ZP8HQ8RZXS | 2 years | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| NID | 6 months | NID cookie, set by Google, is used for advertising purposes; to limit the number of times the user sees an ad, to mute unwanted ads, and to measure the effectiveness of ads. |

| test_cookie | 15 minutes | The test_cookie is set by doubleclick.net and is used to determine if the user's browser supports cookies. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |

| yt-remote-connected-devices | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt-remote-device-id | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt.innertube::nextId | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| yt.innertube::requests | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| DEVICE_INFO | 5 months 27 days | No description |

| loglevel | never | No description available. |

| m | 2 years | No description available. |

Thinkers50 Limited has updated its Privacy Policy on 28 March 2024 with several amendments and additions to the previous version, to fully incorporate to the text information required by current applicable date protection regulation. Processing of the personal data of Thinkers50’s customers, potential customers and other stakeholders has not been changed essentially, but the texts have been clarified and amended to give more detailed information of the processing activities.