Modupe Taylor-Pearce is the founder and CEO of Breakfast Club Africa, a Pan-African organization that supports CEOs with leadership coaching services and knowledge sharing. Modupe has a passion for leadership development that was born out of his experiences as an officer serving in combat in the Sierra Leone Civil War. It continued when he earned his bachelor’s degree at West Point. He has helped over 2000 African leaders to transform the continent through good leadership.

On 15 March 2022, Stuart Crainer and Des Dearlove had Modupe Taylor-Pearce on as a guest in a new session of the Thinkers50 Radar 2022 LinkedIn Live series in partnership with Deloitte.

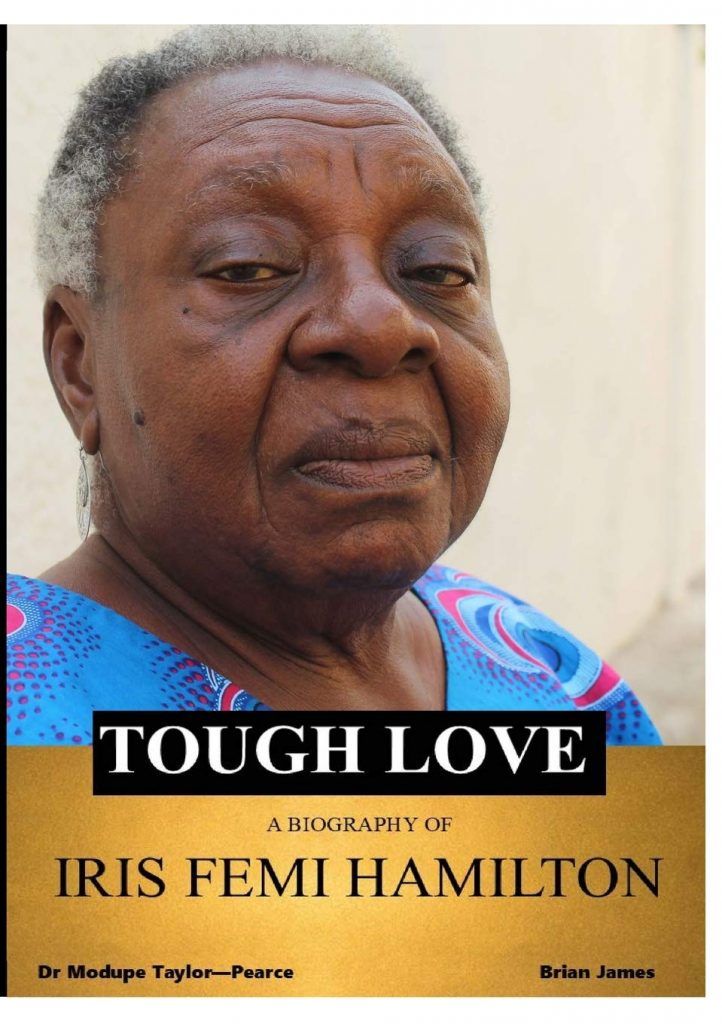

Modupe Taylor-Pearce recently published a biography of Iris Femi Hamilton, Tough Love, (2021) that details the skills one Sierra Leonean used to make her supermarket, Pluris Stores, into a successful business and a business hub in her area.

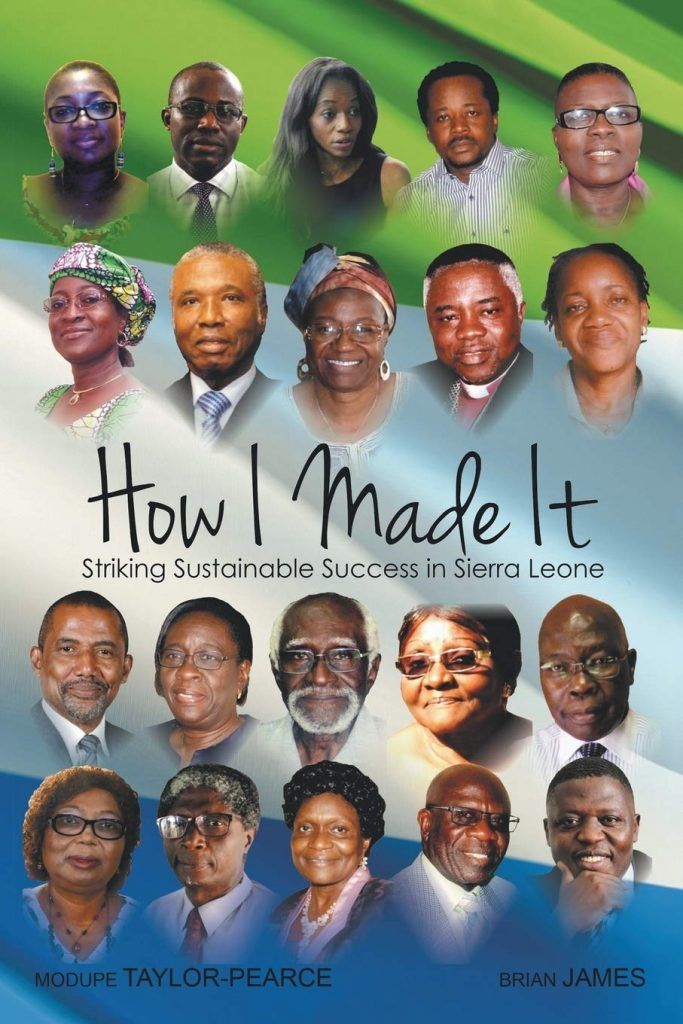

Modupe’s previous book, How I Made It: Striking Sustainable Success in Sierra Leone, shares the secrets of success of twenty accomplished Sierra Leoneans.

Des Dearlove:

Hello, welcome to the Thinkers50 Radar 2022 series, brought to you in partnership with Deloitte. I’m Des Dearlove.

Stuart Crainer:

And I’m Stuart Crainer. We are the founders of Thinkers50, the world’s most reliable resource for identifying ranking and sharing the leading management ideas of our age, ideas that make a real difference in the world.

Des Dearlove:

In this weekly series of 45 minute webinars, we want to really showcase some of those ideas to bring you the most exciting new voices of management thinking.

Stuart Crainer:

So please let us know where you are joining from today and send over your questions at anytime during the session.

Des Dearlove:

Our guest today is Dr. Modupe Taylor-Pearce. Modupe Is a scholar and practitioner of leadership organization and management. He’s also a leadership trainer, coach and facilitator and a managing partner of the leadership development company, CTI Consulting. He has a PhD in leadership from Capella University and a master’s in engineering from Cornell. Modupe is also the first and only person from Sierra Leone to qualify for, attend and graduate from the United States Military Academy at West Point. He is a former military leader with combat experience serving in the Republic of Sierra Leone’s military forces as an infantry officer during the civil war and was shot twice in battle.

Stuart Crainer:

Modupe was the founding dean of the African Leadership University School of Business, and now serves as a visiting professor there. He’s also the founding dean of Cora Coaching Academy based in Rwanda. He currently serves as CEO of Breakfast Club Africa, a Pan-African leadership enhancement organization, which he co-founded and which is now present in eight countries and has impacted over 2000 African leaders with leadership coaching.

Des Dearlove:

Somehow he also manages to find time to curate the maiden Africa Leadership Conference and write books, including most recently a biography of the Sierra Leonian supermarket entrepreneur, Iris Femi Hamilton entitled Tough Love. His previous book, How I Made It: Striking Sustainable Success in Sierra Leone shares the secrets of success of 20 accomplished Sierra Leonians. Modupe, welcome.

Modupe Taylor-Pearce:

Thank you so much Des and Stu, and a special congratulations to you Des for pronouncing the word Sierra Leonians perfectly, you do it even better than most Sierra Leonians. Thank you.

Des Dearlove:

It’s a great pleasure to have you here. Now listen, your passion for leadership it sparkles from you, where does that passion go back to? Let’s go back to the beginning, when did you suddenly become interested in leadership?

Modupe Taylor-Pearce:

You know sometimes one is impacted and doesn’t even realize it. So I remember as a teenager, my father would read these management and leadership books and I thought they were just horribly boring, and I wanted nothing to do with that. Thankfully, he didn’t force them on me, but certainly I think from his example I started to imbibe certain things, but I didn’t really call it leadership, I didn’t understand it for what it was and the same with my mother. But the time when it really hit me was when I was fortunate enough to have the opportunity to attend the US Military Academy and that place is a cradle of leadership, it’s a school of leadership. Many people think it’s a military school, it’s actually really a leadership school. And I got to see everything from good to absolutely fantastic leadership, now that’s where I became more aware.

However, the place where I developed my passion for leadership was roughly six months after I graduated as a newly minted lieutenant and I was thrown into the civil war. And one day I was commanding a whole company or battalion of people, and one of the company commanders that served under me, who unfortunately had a problem with alcohol, led his unit into the zone of another unit at night and they exchanged friendly fire and five young soldiers died.

I ended up rushing there and had to witness and personally help bury those young men, and that’s the day that leadership hit me. Because I found myself asking myself the question, “What did these young men do to deserve this? What was their crime?” And I realized that their only crime was that they served under an abysmal leader. And that’s when I came to realization that when leaders make poor or bad decisions, their people suffer. And when they make wise or optimal decisions, their people’s lives are improved. And that’s when my passion really came through because I swore to myself that I was going to dedicate my life, to making sure that as few as possible young Africans would have to have their lives robbed from them, or their livelihood robbed from them because they were serving the leaders that were making poor decisions.

Des Dearlove:

We did some work a few years ago with a former brain surgeon who was very passionate about leadership and he was coming up with sort of a similar issue, but from another side. And his mantra was in an operating theater leadership saves lives, and it’s a sort of a flip side of a not dissimilar point really, is that it’s not academic whether you have good leadership or not, in certain situations, obviously, really mission critical situations it’s about life and death, so makes all the difference.

Modupe Taylor-Pearce:

Absolutely, and if I may add one more point, part of the reason why many people aren’t aware of how important it is because in normal life, there’s a longer lag time between the decision that a leader makes and the outcomes, whether positive or negative and because of that, we don’t really tie cause to effect. Now certainly in a surgery, brain surgery, you can definitely see it. You get the outcomes within 24 hours or sometimes less, same with in a war zone. But the reality is that we see that in countries, we see that everywhere. And I can give you example after example of how leaders who have made optimal decisions, we’ve seen their communities, their companies, their countries become better or their families become better and vice versa.

Stuart Crainer:

It’d be good to welcome all the people joining us. We’ve got somebody from Algeria in India, Lagos, Lusaka in Zambia, great global audience. Modupe take me back to when you walk through the doors of West Point, what did that feel like, it must be daunting.

Modupe Taylor-Pearce:

It was, it was a whole new world. There I was a kid from Africa – I had never been to the United States before, I had lived in Sierra Leone, in Ghana, in Kenya, been to three or four other African countries. But not only did I go to the United States for the first time, but I went to the United States straight into West Point, it was a completely different world. But thankfully, because of the great leadership there, they had prepared for us. They didn’t give us a lot of time to reflect on what was happening, they wanted us to learn, to react, to react, to react as followers and to train our minds into a number of things. But at the same time, over the four years, they gave us support structures so that when you needed counseling, you needed mentorship, one needed that kind of support it was available. And I must say I still rank it as the number one leadership development institution in the world.

Des Dearlove:

In the UK there’s Sandhurst which, again, people speak well of, I imagine it’s the same at West Point, the sort of the servant leader model, you lead to serve those who follow, which obviously is a way of looking at it, there’s a humility to it and a sense of duty that comes with that. The other thing that I know you’re really passionate about is coaching and the role that can play in terms of developing leaders, can you say a little bit more about that?

Modupe Taylor-Pearce:

Yes, indeed. And incidentally, when I was at West Point, we used to have annual competitions between the West Point cadets and the Sandhurst cadets. And I have to confess Des, that half the time the Sandhurst cadets kicked our butts.

Des Dearlove:

Only half the time.

Modupe Taylor-Pearce:

So clearly they’re doing something really well there. I became exposed to coaching at a time when I didn’t even know what it was called. I was with an organization, we were doing turnaround consulting and they would do leadership training, but then they would follow it up with what they called one-on-one follow ups. Now I was just watching this and I didn’t really understand it, but the time I really came to understand it’s value was in about 2005, when I got my first CEO opportunity, I was picked to run a small-ish logistics company in California and the chair said, “I want you to join this group.”

I said, “Okay, sir, what is this?” And it was a group where we had both peer learning and they provided coaching. And it wasn’t cheap by any stretch of the imagination, we paid about $10,000 a year for the fees. But I can tell you that over the next five years, there were at least three or four key decisions that I made differently from how I would’ve made them, that impacted the fortunes of this company, which we were able to turn around. Now here’s what then happened next. After that five or six years, I moved back to Africa fresh off the glow of having turned around a $20 million company. And I started two businesses over the next two years, they failed spectacularly, like serious failures. So two years later or two and a half years later, I’m licking my wounds, doing a bit of consulting here and there to try to fill up the hole that I had dug in our family finances and thinking, “What happened to you Modupe? What happened? Did you just go stupid all of a sudden?”

And what I realized was that what I did not have was the coaching and the peer learning. And because of that, I ended up making suboptimal decisions from a place of lack of awareness, that then led to these companies not being successful. They were not successful not because I woke up every day saying, “Gee, let me see how I can screw up these companies.” But they were unsuccessful because I made what I thought were optimal decisions, but because of my lack of awareness, because I didn’t have a thought partner to support me, I ended up making the wrong decisions. And that for me is where coaching comes in because a coach is a thought partner, first of all. Somebody who supports you in thinking through some of those thorny issues, but does it in a way that doesn’t tell you what to do, that’s very important, but they ask you questions that get you to think through the possibilities.

And the second part of what a coach does, which was so important for me is that they are an accountability partner as well. So that once you’ve thought through what you want to do and decided to do something, that you follow through with it, because we all know that the road to hell is built with good intentions. And so that role of a coach is very important and it’s not a surprise that today 80, 90% of Fortune 1000 companies, CEOs have a coach and we can see the impact of that all over the world.

Stuart Crainer:

I like the idea of an accountability partner, everyone needs one.

Modupe Taylor-Pearce:

Yes, we do. Indeed.

Stuart Crainer:

Coaching has become acceptable and popular certainly in America, I would say less so certainly in Europe. And how about in Africa and in Sierra Leone, what’s the attitude to coaching there?

Modupe Taylor-Pearce:

For the most part it’s not popular and that’s because of a lack of awareness and in some cases a misunderstanding about what it is. There’s a large swath of the leadership population that aren’t even of what coaching is, and then there’s another large swath that think it’s remedial training for mediocre leaders. So the first thing that happens when you talk about coaching is they’re like a little bit shocked, “What do you mean? Do you know who I am? What do you think is wrong with me?” So this is one of the huge challenges and here’s where it becomes so important Stu and Des. Over the last 40 years companies in Africa that have been owned by Africans, majority owned, when comparing their growth rate to companies in Africa that are owned by non-Africans, the comparative growth rate of the two companies is one to three.

In other words, companies in Africa owned by non-Africans are growing on an annual basis, three times as fast as the ones owned by Africans. What’s the reason for this? The reason comes down to the coaching that they get, as well as some peer learning. Because here’s what happens when you’re appointed to be the head of Heineken in Kenya, or the head of Standard Bank in Malawi, you’re given a coach, you’re assigned one, it’s often not even a choice that you get. By contrast when you become the head of the local brewery or drink company or The Bank of Kenya, it’s a time of celebration.

And all of a sudden everybody assumes that by assuming that position you’ve been given a mantle of brilliance that just tells you, “Wow, you know everything to do,” when that couldn’t be farther from the truth. So the lack of support that leaders in Africa have, is leading to them making suboptimal decisions on a consistent basis. And then they spend about half of their time trying to cover up the outcomes from these suboptimal decisions, and that’s such a crime, it’s such a missed opportunity, and that’s what I’m passionate about changing.

Des Dearlove:

Is this partly a role models thing? Because if leaders in Africa look to other African leaders and they’re not using coaches, it becomes almost a self-fulfilling prophecy, that’s not how African leaders lead. Is that something that needs to change, do we need to sort of widen our remit in terms of who we see as role models?

Modupe Taylor-Pearce:

In many ways it is, but as you’ve already pointed out, the challenge is that the very role models don’t know what coaching is. So the challenge we have is almost similar to the challenge that or Mo Ibrahim had when he introduced the cellphone to Africa. When people were saying, “What do I need this for? Spend a lot of money for this little thing, so that what I can talk to somebody? I have 12 children, if I need to send a message, I’ll send them out there. One of them will go and do that.” But of course, once you’ve got some early adopters and people start to experience the value, then it grows.

And today in Africa, we do have some early adopters. Sadly, they are more along the lines of those people running multinational companies or branches of it. But as we continue to get the word out, and as we continue to develop and train world class coaches in Africa. And as we continue to bring them together under a brand like BCA, so that people are more aware, then we are going to reach that inflection point, where someday having a coach will not just be a luxury for a leader of an organization, it’ll actually become a right of passage.

Stuart Crainer:

We’re really delighted, we’re joined by Nankhonde Kasonde-van den Broek, who won our coaching award at the Thinkers50 2021, she’s joining us from Zambia. And she agrees that coaching in Africa is often seen as remedial or punitive, “And hopefully your work is helping us move that Modupe.” Tell us about the Breakfast Club Africa, you alluded to it then, how did that start and what does it do, because some of our viewers might not be up to date with its work.

Modupe Taylor-Pearce:

Indeed, thank you so much. Indeed, Breakfast Club Africa started out of the very need I spoke about, where I realized that I needed a space where I could learn with other leaders and also receive coaching. And after looking in Sierra Leone, in Ghana and in the Malawi, and in Rwanda and not finding it, I came to the realization that if you need it, you better create it, so we went about doing that. And when we first started we would meet in the mornings over breakfast, hence the term Breakfast Club Africa. Now, since then, we’ve grown now in five years where we’ve got about 35 coaches across 13 different countries in Africa, and many of our meetings and our gatherings and our coaching are done virtually, and they’re not necessarily done in the morning. So we’ve actually changed our name now to BCA, which is Breakfast Club Africa, BCA Leadership, which is more in tune with where we’re going and what our focus is.

But truly today we have to date we’ve impacted over 2000 leaders, who employ our services for peer learning or knowledge sharing with other peers and for executive coaching. And our vision is that by 2030, we would’ve impacted a million African leaders in both the public sector as well the private sector, we’ve started in the private sector, we’re now venturing into the public sector and the nonprofit sector. Because we are keenly aware that it’s going to take leaders making optimal decisions in all three sectors from Africa to achieve its true potential and become that middle income continent by 2030, that we are passionate about driving it towards.

Des Dearlove:

At the start when we were introducing you, we mentioned a couple of the books you’ve written, again, there’s an interesting theme that seems to run through that. There’s a kind of a celebration of the success of Sierra Leonians if you like, in one case with Iris Femi Hamilton, an entrepreneur who started supermarkets. But also in the previous book also celebrating how these people have achieved success, are there distinctive lessons from that or is that just sort of the same as you would expect anywhere else, is there other special qualities to Sierra Leonians who are successful?

Modupe Taylor-Pearce:

Indeed, there are, having said that though, I found that those qualities are quite similar to the same qualities that make people successful in other places. I did those books because I grew up, let not say grew up. In my 20s I became passionate about reading about successful people. And so I read the books written by Jack Welch, by Nelson Mandela, reading about Richard Branson, because I figured the best way to get to where you want to go is to learn from those who walked that path. And in many ways I wanted to do the same thing for people in Sierra Leone, because there is the temptation when you read about somebody in another country to say, “That works there, but my situation could be different.” But the more I’ve done this and I do plan on doing some books that are more Pan-African.

The more I’ve done this, the more I’ve come to the realization that the secrets to success are common, they’re the same thing regardless of where you are. It’s being vision focused, being very clear about where you’re going in the long term. It’s being reliable and trustworthy, people have to know that your word is your bond and they have to trust you, otherwise they won’t invest their time, talents or treasure in you or in your big plan. And the third is being a lifelong learner, recognizing the fact that you don’t have the skills or the knowledge that you need to achieve the vision that you want to achieve, and therefore you have to be constantly searching out and growing in that direction. Because what then happens is that as you are learning and acquiring new knowledge and skills, the people who need to invest their time, talents and treasure in your vision will actually appreciate that and start to gain more confidence in your ability to actually make that vision a reality.

And ultimately that’s what success is, it’s the achievement of your vision, whatever it is. Nelson Mandela was successful because he achieved a freed South Africa, that was his vision, his vision had nothing to do with, “I want to make a billion dollars.” It was a freed South Africa. Richard Branson’s definition of success was different, but he achieved it and the same thing with Jack Welch. So whatever is your vision, achieving that is what success is, and the first step is you have to have one, because you’d be amazed how many people go through life and they have no clue what they want to achieve in life. They’re just floating around like a boat in the middle of the water and just being taken around by any window or wave. And secondly, be a lifelong learner. And thirdly, be trustworthy, your word has to be your bond, character and reliability.

Stuart Crainer:

I think we’re all marking ourselves on those as you’re speaking Modupe. I always think sustaining curiosity, when you talk about lifelong learning, sustaining curiosity is really difficult. You don’t meet many people who are in their mid 80s or older who are still curious, it’s a hell of a difficult thing to put off and sustain.

Modupe Taylor-Pearce:

It is and that’s why quite frankly, sorry to interrupt, I was just going to say, that’s why the world is where it is because a lot of us become intellectually lazy and so we don’t fulfill our potential. Or as one famous person said the wealthiest place in the world is the grave because it’s where all the unfulfilled dreams and visions lie.

Stuart Crainer:

We’re joined by Simone Phipps from Atlanta, Georgia, and Simone is co-author of the book African-American Management History, which is a really good book, which highlights some of the African American management pioneers. And one of the idea’s she’s been championing is cooperative advantage and has drawn attention to the tradition of ubuntu in Africa. And I wonder is there an appetite in African management and African leadership, is there an appetite for collaboration which you think is bigger than in the states or elsewhere?

Modupe Taylor-Pearce:

This is a very interesting question and my perspective may be a bit controversial. Now in Africa my experience is that we love to talk about ubuntu and collaboration, we love to talk about it, but the truth is we don’t practice it very much. Now there are reasons for that and if you read history, you can read the fact that going even to recent history with the colonialism. And the reason why Africa was colonized by Europe was because of a strategy of divide and conquer, pit them against each other and that way it’s easy for a country that’s 100th of the size of Africa to conquer that place. But the reality is that whatever the reasons are, today many Africans find it difficult to trust each other enough to collaborate, because for collaboration to happen there has to be trust, I have to be willing to be vulnerable.

And you can see it today, even in the Africa Free Trade agreement, which was signed and ratified two, three, four years ago. And even to now we’re still struggling to implement the Free Trade agreement. Why? Because it requires trust. Because when one country you say, “Bring down your trade barriers,” it means that, yes, there may be a short term loss, there’s a risk, and how well do I trust my fellow African? This is one of the challenges. So yes, we aspire to ubuntu, we aspire to collaboration, but all you have to do is look at our elections, which generally are consistently along trial lines to understand that it’s still an aspiration, but not yet an actuality.

Des Dearlove:

Yeah. I think there’s a big challenge to trust in general, although obviously Africa has its own special history and reasons for not perhaps being quick to trust, but I think there’s a shortage of trust everywhere. Tell me though, is there a distinctive African management philosophy, if not necessarily a distinctive way of operating, is there a different philosophy? We have the sense that the West or that even America is moving away from the whole shareholder value model, and we’re pleased to see that especially in Europe where we’ve been trumpeting that for some time. But do you get a sense in Africa that there’s a different way of looking at the world from a management point of view?

Modupe Taylor-Pearce:

In some ways, yes, there is. I would say that it’s due to certain realities that we have and I’ll just share maybe a three or four of them. One of the realities is the lack of social safety nets. So when it comes to how do you manage resources, because we don’t have good social safety nets, that’s a problem. I was speaking to a colleague of mine from Scandinavia and he said something about, “I think I’m going to take a year off just to get my bearings together.” And I kind of smiled and said, “I wonder how many Africans afford to take a year off.” But this is a reality that then colors how you manage resources. Because when people in Africa are literally two weeks or four weeks paycheck away from being homeless or wifeless, that changes how they’re going to be with resources.

Another reality that affects how you manage in Africa is the fact that for now in most African countries, the state controls 60 to 70% of the economy and the government, which means that pretty much you cannot help but have to deal with public sector. In the US, in the UK, you could literally have your small business, you could make a million pounds and never really deal with a public sector person, with a regulator for the most part, but that’s just not going to happen in Africa, so there are certain realities. And of course, public sector officials are driven by different factors. A third factor is let’s call it the social cultural situation in Africa, which is as follows. You have your friend circle, everybody has a friend circle, then you have a family circle, everybody has family, and then you have what I may call a work circle, you got colleagues.

Now in the UK, certainly in the US, for most people, those three circles don’t intersect that much. The people you might meet in terms of friends or maybe even church or whatever, are different from your family and maybe different from work. In Africa those three circles many times sit right on top of each other. So in other words you may be working, your colleague may go to the same, A, may be a family member, B, may go to the same church as you, and so that creates certain unique dynamics when it comes to managing resources, especially managing people.

Because when you want to think about hiring or firing or disciplining or motivating, you have to think much more than just the work, you have to understand all of those aspects. And it’s one of the reasons why quite frankly, leading people in Africa is a bit more complicated than leading elsewhere, because you have to think of so many of those moving parts when making decisions. And that’s why quite frankly, in Africa, even more than in the United States every leader needs a coach.

Stuart Crainer:

And I presume then Modupe you have a coach and how long have you been working with them, and what kind of insights have you garnered from working with your coach?

Modupe Taylor-Pearce:

So I personally have a coach and certainly I wouldn’t be here if I didn’t have a coach, I’m a grateful recipient of our own services, and that helps me with making certain key decisions. I also serve as a coach and have been blessed to be able to support a number of leaders in various countries in Africa. And I think what I would say is and I’ll illustrate it with a bit of a story. There was a certain head of a back who retired from the bank. He had served in the bank for 30 years and finally as the CEO. Now in his last five years as the CEO, the bank grew a grand total of 0.5%, but it was an African owned bank, a government bank. And when he retired, he was celebrated and feted. And I thought to myself, “What a missed opportunity.” Now during the same five years when he was the CEO, the competitor banks, two of them were owned by Nigerians, one of them owned a Pan-African bank, they grew over the five years at an average clip of 16%.

And yet this gentleman was feted and this gentleman will go into retirement not even realizing that he did a crappy job, that he did not do his job to create the jobs for another generation, and it is this that fuels me. And thankfully I’ve been able to coach people whose decisions have made the difference between a factory closing down, shutting down, or a factory being reinvested in in Africa. These are the kinds of things that make me get up in the morning, because I realize that what we’re doing Des and Stu is not for us. The reality is most of us are at the age where frankly we don’t need more, we need less, we need to eat less. We need a smaller house because our kids have left the house. So it’s not for us, it’s for us to create a better future for our grandchildren quite frankly and that’s what I’m passionate about.

Des Dearlove:

Now, as you were speaking then just a little bit you reminded me of talking to Marshall Goldsmith when he gets going, presumably you know Marshall reasonably well. He’s taken the executive coaching, he really rode that wave because it wasn’t so long ago that coaching wasn’t as well established because of the same resistance within American corporations, it was seen as a remedial thing, it was seen as, “I must be failing, what do I need a coach for?” But Marshall has a very clear model of coaching and he’s not shy to tell everybody what it is, what’s your model for coaching? How does it work in your organizations, is there a particular model or does it tend to depend on the individual?

Modupe Taylor-Pearce:

So I’m so glad you mentioned Marshall because I’m very keenly aware that we stand on the shoulders of giants. And in many ways Marshall has walked the path that I’m trying to walk in terms of making coaching something that, as you said, is seen as the breakfast of champions, not losers. And so in terms of what he has done and I admire his model and I love it, and I think it’s absolutely appropriate for the United States. In Africa, in many ways in terms of the actual coaching, I generally follow the GROW Model, but I’m very familiar with other types of coaching models. And for those who may never have heard of coaching GROW is G-R-O-W, and you can just Google it and you’ll find out more rather than me boring you with the details of that, but there are other models that work just as well.

And the key is that in coaching, the coach for me has to be always focused on your role as a facilitator of success. Your role is to help the client achieve their goals, that’s it. And my role is to ensure or find the best way for the client to reach that goal, whatever that goal is. And sometimes for some clients, we spend a whole lot of time just figuring out what that goal is. You’d be surprised how many people don’t really know what they want, and that alone is uncomfortable for them. And for others they know what they want, they just don’t know how to get there and they need some support in getting there, but as long as we get them there.

Now in terms what we do with clients, it’s different for every client, because for some client you’re dealing with homegrown entrepreneurs, self-made successful people who may or may not have had excellent formal education and you’re supporting them. For others you’ve got people who maybe just got transported into Africa from Europe or South America, and this is their first time in the continent and they suddenly have a big responsibility, and then you have everything in the middle of that. And part of my role as the coach and all of the BCA coaches is to support these people with the thinking, the awareness, the focus and the accountability, so that they can make those decisions that will yield success for them and for their organizations.

Stuart Crainer:

Yeah. Thank you everyone for your comments as we’ve been to talking and thanks Nankhonde, thanks Simone, coming back on some of the points Modupe has raised. There’s a question from Anastasia in Greece, and she talks about, “How do you build a resilient mindset?” Because I think even with the best coach in the world and even with a great leader there’s ups and downs, there’s pitfalls and things change and lots of different difficult situations, but how do you build that resilience? Not everybody can join the army, which provides a certain sort of resilience, but in organizational situations, you also need it.

Modupe Taylor-Pearce:

I have to confess that when you said we have a question from somebody in Greece, I naturally became nervous because I was thinking about your previous session, where you had somebody ask you the question in Greek, so thank God it’s something along my alley. There’s no doubt that resilience is one of the valuable qualities in today’s world. And the resilient mindset comes from in my view a number of things. Number one, keeping your eye on the prize, keeping your eye on the vision. And number two, just taking one step at a time, equipping yourself, which is part of the lifelong learning, just one step at a time. If you look at the distance, you get discouraged, but if you just keep going every day and you learn, you’ll suddenly be surprised. And the key to doing all those things and not listening to the naysayers and the negativity and the indications and the problems and the obstacles is having a coach, because the coach helps you to remind yourself of why you started this journey in the first place.

And I am exhibit number one, I cannot tell you how many times I’ve called my coach and I’ve literally just had a pity party for myself. And I’m like, “Oh my God, I hate this. I don’t know why I even started this journey. This is stupid, I’m just wasting my time. Right now I just-” And the coach helps you to refocus and keep your eye on the prize and to take some positive action towards it and that’s what resilience is. Resilience is simply refusing to stay still even when the storm is around you, it’s just saying, “I can’t even see where I’m going for sure, but you know what, I’m still going to keep moving. I can’t even see how I’m going to make it, but I’m still going to keep moving,” that’s what resilience is. It’s trusting that the dam will break, resilience is investing in a continent where everybody said, “Are you kidding, don’t waste your time. People in Africa cannot afford to pay for SIM cards, much less cell phones,” that’s what Mo Ibrahim was told.

Now of course those people now will never confess to having said that when we know the future. Resilience is Nelson Mandela sitting in jail and saying there will be a free South Africa, at a time when he was being called a terrorist by well-meaning people. Resilience is believing that someday having a coach will become not the exception, but a right of passage for every leader in Africa, even at a time when half the leaders are saying, “Eh, nice try. I know what I’m doing here, that’s why they elected me.” That’s resilience, but it doesn’t always come from inside, we all need support and that’s where a coach comes in.

Des Dearlove:

Fantastic. We’re running out of time. We’ve landed just where we would’ve hoped we might have land, but just say a couple of words about your own vision, because I get the sense you exude the passion. And that one million coaches for African leaders that I think you mentioned, I suspect that’s linked very much to your own personal vision, can you just say a couple words about that? And perhaps tell us also where people can go to get resources, people who are interested in finding out more about your work.

Modupe Taylor-Pearce:

Indeed. I’m amazed Des at how frankly the world has changed. In 1990, when I was applying to the US Military Academy, through the army, I literally had to spend about $25 to make a 10 minute phone call to the United States, and by the way that was $25 and half the day to travel to somewhere. And today I’m sitting here talking to people across the world for a cost that is a fraction of a dollar, and so there’s so much that can happen in just 30 years. And this is where part of my faith comes from because that transformation occurred because there are people who believed in something that wasn’t yet possible. My vision is that Africa is going to be a middle income continent by 2030 and a high income continent by 2045.

And by 2030, I will be close to 60 years old, in 2045 I will be about 75. So if God gives me life and health, I will see the day when Africa will be a high income continent. Such that when I tell my grandchildren about how, “When we used to go to school and I would walk five miles from where there was a bus.” My grandchild will say to his brother, “Grandpa, he’s got all kinds of tall tales, that’s what he likes to do.” Can you imagine, that’s my vision is that there will come a day soon when it would be just crazy to think about starving kids in Africa. That coups will be something we read about in books and say, “Are you kidding? Why didn’t they just organize a social experiment and do a quick snap poll, so they could figure out how to change what the go was doing?”

My vision is that every child, every African child, regardless of who their parent is, that is born today, by the time they grow up to be 21 years old would have had access to world class education, world class healthcare, and be able to get a job without having to leave the shores of Africa. That when they leave the shore of Africa, it’s because they said, “Oh, you know what, let’s go vacation somewhere else for a change.” That’s my vision. And the way we’re going to get there is by getting leaders to make consistently optimal decisions.

And for that to happen, we wants to reach the point where one million leaders have been impacted by BCA. And if you are out there and you are a leader and you don’t have a coach, I urge you to get a coach, not for you, not for your benefit, but for the benefit of those people who depend on you for that service that is called leadership because they deserve better. They deserve to see you do your best and for that, I encourage you just go to bcaleadership.com, bcaleadership.com and that’s all you have to do. And you can just follow the prompt and once you follow the prompts, we can get you a coach. Send us a message and we’ll hook you up so that you’ll have a coach, so that the people who depend on you, whether it’s your children, your employees, your communities, they will be able to say later on in life that, “Wow. I served under an awesome leader.” Thank you.

Stuart Crainer:

No, thank you, Modupe. That was Dr. Modupe Taylor-Pearce Jr. Fantastic session, really inspiring what a better world that would be. Modupe we really thank you for sharing with us today and thank you for all the people from throughout the world who joined us. We hope you check out Modupe’s website and check out his inspiring work. And he will definitely keep us posted what he’s doing over the next few years and we will do the same with you. So we’re away next week, but we’ll be back in two weeks for another session. Thank you everyone for joining us and thank you, Modupe.

Des Dearlove:

Thank you.

Modupe Taylor-Pearce:

Thank you Des and Stu, and may the world be a better place because of what Thinkers50 is doing. Thank you.

Stuart Crainer:

Thank you.

Des Dearlove:

Thanks.

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| LANG | 9 hours | Linkedin set this cookie to set user's preferred language. |

| nsid | session | This cookie is set by the provider PayPal to enable the PayPal payment service in the website. |

| sp_landing | 1 day | The sp_landing is set by Spotify to implement audio content from Spotify on the website and also registers information on user interaction related to the audio content. |

| sp_t | 1 year | The sp_t cookie is set by Spotify to implement audio content from Spotify on the website and also registers information on user interaction related to the audio content. |

| tsrce | 3 days | PayPal sets this cookie to enable the PayPal payment service in the website. |

| x-pp-s | session | PayPal sets this cookie to process payments on the site. |

| __cf_bm | 30 minutes | This cookie, set by Cloudflare, is used to support Cloudflare Bot Management. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| l7_az | 30 minutes | This cookie is necessary for the PayPal login-function on the website. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| CONSENT | 2 years | YouTube sets this cookie via embedded youtube-videos and registers anonymous statistical data. |

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_10408481_1 | 1 minute | Set by Google to distinguish users. |

| _ga_ZP8HQ8RZXS | 2 years | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| NID | 6 months | NID cookie, set by Google, is used for advertising purposes; to limit the number of times the user sees an ad, to mute unwanted ads, and to measure the effectiveness of ads. |

| test_cookie | 15 minutes | The test_cookie is set by doubleclick.net and is used to determine if the user's browser supports cookies. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |

| yt-remote-connected-devices | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt-remote-device-id | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt.innertube::nextId | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| yt.innertube::requests | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| DEVICE_INFO | 5 months 27 days | No description |

| loglevel | never | No description available. |

| m | 2 years | No description available. |

Thinkers50 Limited has updated its Privacy Policy on 28 March 2024 with several amendments and additions to the previous version, to fully incorporate to the text information required by current applicable date protection regulation. Processing of the personal data of Thinkers50’s customers, potential customers and other stakeholders has not been changed essentially, but the texts have been clarified and amended to give more detailed information of the processing activities.