Virtual Event

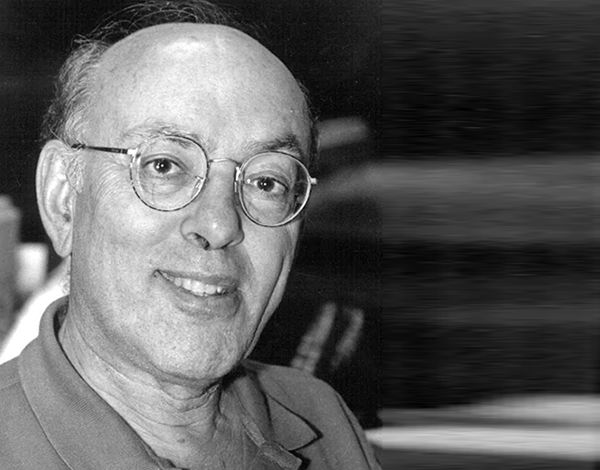

To celebrate Henry Mintzberg receiving the Thinkers50 Lifetime Achievement Award we take a look at his classic book: The Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning.

Henry Mintzberg’s The Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning (1994) reflects a general dissatisfaction with the process of strategic planning – research by the US Planning Forum found that only 25 percent of companies considered their planning processes to be effective and OC&C Strategy Consultants observed that ‘the humane thing to do with most strategic planning processes is to kill them off’.

Mintzberg has long been a critic of formulae and analysis-driven strategic planning. In The Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning, he remorselessly destroys much conventional wisdom and proposes his own interpretations.

He defines planning as ‘a formalized system for codifying, elaborating and operationalizing the strategies which companies already have’. In contrast, strategy is either an ‘emergent’ pattern or a deliberate ‘perspective’. Mintzberg argues that strategy cannot be planned. While planning is concerned with analysis, strategy making is concerned with synthesis. Planners are not redundant but are only valuable as strategy finders, analysts and catalysts. They are supporters of line managers, forever questioning rather than providing automatic answers. Their most effective role is in unearthing ‘fledgling strategies in unexpected pockets of the organization so that consideration can be given to (expanding) them’.

Mintzberg identifies three central pitfalls to today’s strategy planning practices.

First, the assumption that discontinuities can be predicated. Forecasting techniques are limited by the fact that they tend to assume that the future will resemble the past. This gives artificial reassurance and creates strategies which are liable to disintegrate as they are overtaken by events.

He points out that our passion for planning mostly flourishes during stable times such as in the 1960s. Confronted by a new world order, planners are left seeking to re-create a long-forgotten past.

Second, that planners are detached from the reality of the organization. Mintzberg is critical of the ‘assumption of detachment’. ‘If the system does the thinking,’ he writes, ‘the thought must be detached from the action, strategy from operations, (and) ostensible thinkers from doers. … It is this disassociation of thinking from acting that lies close to the root of (strategic planning’s) problem.’

Planners have traditionally been obsessed with gathering hard data on their industry, markets, competitors. Soft data – networks of contacts, talking with customers, suppliers and employees, using intuition and using the grapevine – have all but been ignored.

Mintzberg points out that much of what is considered ‘hard’ data is often anything but. There is a ‘soft underbelly of hard data’, typified by the fallacy of ‘measuring what’s measurable’. The results are limiting, for example a pronounced tendency ‘to favor cost leadership strategies (emphasizing operating efficiencies, which are generally measurable) over product-leadership strategies (emphasizing innovative design or high quality, which tends to be less measurable)’.

To gain real and useful understanding of an organization’s competitive situation soft data needs to be dynamically integrated into the planning process. ‘Strategy-making is an immensely complex process involving the most sophisticated, subtle and at times subconscious of human cognitive and social processes,’ writes Mintzberg. ‘While hard data may inform the intellect, it is largely soft data that generate wisdom. They may be difficult to “analyze”, but they are indispensable for synthesis – the key to strategy making.’

The third and final flaw identified by Mintzberg is the assumption that strategy making can be formalized. The left-side of the brain has dominated strategy formulation with its emphasis on logic and analysis. Overly structured, this creates a narrow range of options. Alternatives which do not fit into the pre-determined structure are ignored. The right -side of the brain needs to become part of the process with its emphasis on intuition and creativity. ‘Planning by its very nature,’ concludes Mintzberg, ‘defines and preserves categories. Creativity, by its very nature, creates categories or rearranges established ones. This is why strategic planning can neither provide creativity, nor deal with it when it emerges by other means.’ Mold-breaking strategies ‘grow initially like weeds, they are not cultivated like tomatoes in a hothouse. … (They) can take root in all kinds of places’.

Strategy-making, as presented by Mintzberg is:

The Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning attracted a great deal of attention and some vituperative debate. ‘In many ways, the book’s title should be reversed to the fall and rise of planning,’ observed Christopher Lorenz in the Financial Times arguing that the book represented the ‘mellowing of Mintzberg’.

Mintzberg’s work brought a spirited response from the defenders of strategy. Andrew Campbell, co-author of Corporate-Level Strategy, wrote: ‘Strategic planing is not futile. Research has shown that some companies – both conglomerates and more focused groups – have strategic planning processes that add real value.’ The solution, according to Campbell is not to deem planning an inappropriate corporate activity but will only occur when ‘the corporate center develops a value-creating, corporate-level strategy and builds the management processes needed to implement it’.

As the debate rumbles on, Mintzberg increasingly expanded his intellectual horizons to talk about what he calls “nuanced managing” — “I don’t think it is a better way of managing, I think it is managing,” he explains. “I think all decent management is nuanced. Bad management is not nuanced; bad management is categorical. Nuanced management is about getting involved, knowing the business, knowing what’s going on day-to-day. For me it’s all about getting past all the nonsense that passes for management. It’s getting in touch, knowing what’s really going on, being responsive – and responsible.”

Mintzberg has reflected that he has spent his public life dealing with organizations, and his private life escaping from them. “I just don’t like big hierarchical organizations,” he told Thinkers50 co-founder Des Dearlove in 2002.

“In the past some large organizations treated people paternalistically, but reasonably decently. But many have destroyed that contract. It’s significant that the two most popular management techniques of all time – Taylor’s work study methods – to control your hands – and strategic planning – to control your brain – were adopted most enthusiastically by two groups, communist governments and American corporations.”

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

Thinkers50 Limited

The Studio

Highfield Lane

Wargrave RG10 8PZ

United Kingdom

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| LANG | 9 hours | Linkedin set this cookie to set user's preferred language. |

| nsid | session | This cookie is set by the provider PayPal to enable the PayPal payment service in the website. |

| sp_landing | 1 day | The sp_landing is set by Spotify to implement audio content from Spotify on the website and also registers information on user interaction related to the audio content. |

| sp_t | 1 year | The sp_t cookie is set by Spotify to implement audio content from Spotify on the website and also registers information on user interaction related to the audio content. |

| tsrce | 3 days | PayPal sets this cookie to enable the PayPal payment service in the website. |

| x-pp-s | session | PayPal sets this cookie to process payments on the site. |

| __cf_bm | 30 minutes | This cookie, set by Cloudflare, is used to support Cloudflare Bot Management. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| l7_az | 30 minutes | This cookie is necessary for the PayPal login-function on the website. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| CONSENT | 2 years | YouTube sets this cookie via embedded youtube-videos and registers anonymous statistical data. |

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_10408481_1 | 1 minute | Set by Google to distinguish users. |

| _ga_ZP8HQ8RZXS | 2 years | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| NID | 6 months | NID cookie, set by Google, is used for advertising purposes; to limit the number of times the user sees an ad, to mute unwanted ads, and to measure the effectiveness of ads. |

| test_cookie | 15 minutes | The test_cookie is set by doubleclick.net and is used to determine if the user's browser supports cookies. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |

| yt-remote-connected-devices | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt-remote-device-id | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt.innertube::nextId | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| yt.innertube::requests | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| DEVICE_INFO | 5 months 27 days | No description |

| loglevel | never | No description available. |

| m | 2 years | No description available. |

Thinkers50 Limited has updated its Privacy Policy on 28 March 2024 with several amendments and additions to the previous version, to fully incorporate to the text information required by current applicable date protection regulation. Processing of the personal data of Thinkers50’s customers, potential customers and other stakeholders has not been changed essentially, but the texts have been clarified and amended to give more detailed information of the processing activities.